For the purposes of an audio podcast, some of the content of the following interview was edited out of the final cut. Here is the full text. To see what was eventually kept, please see both of the Tokushikai Canada podcast videos on the Media page.

__________________________________________________

Tokushikai Canada’s “Inside Look Podcasts 005 & 012”

Interview with Douglas Tong

Full text

copyright © 2021 Douglas Tong, all rights reserved.

———————————————————————————————————–

Inside Look Podcast 005 – Douglas Tong (Yagyu Shinkage Ryu) Canada

Introduction

Today, we’re speaking with Douglas Tong Sensei from Orangeville, Canada.

Tong Sensei lived in Japan for many years and has studied traditional Japanese sword arts including Katori Shinto Ryu, Ono-ha Ittō Ryu, Muso Shinden Eishin Ryu, and Yagyu Shinkage Ryu for over 30 years.

Tong Sensei has a Master’s Degree in Education and teaches on the front line of public education.

In this stimulating conversation, we talk about the role of Japanese culture in martial arts, and the complexities and challenges for students of understanding and abiding by these traditions. So without further ado, please enjoy this conversation with Tong Sensei.

———————————————————————————————————–

Tong Sensei, maybe you can start us off by telling us a little bit about who you are, where you came from, and the major life events that have put you where you are today as an instructor and promoter of several traditional Japanese martial arts.

First off, I would like to thank you for having me on this podcast. It is a great honour. I really appreciate the chance to talk a little bit about Japanese martial arts and culture and the role it plays.

A major life event. Yes. That’s a good place to start.

My journey into this world of kenjutsu began quite by accident about a month after I had arrived in Japan. It was a warm summer day and I was waiting for my train at Fujisawa Station to go to work. Along comes a gaijin which means in Japanese a foreigner or in this case, a Westerner. Anyway, along comes this big gaijin strolling down the platform and he stops by me. He looks me up and down and asks me quite directly, “You aren’t Japanese, are you?” I was astounded. I am of Chinese descent and was dressed in a business suit so I thought I looked like all the other Japanese businessmen on that platform that day. I said, “No, I’m from Canada.” And from then on, we struck up a long conversation. As it turned out, this gaijin was Pat McCarthy, a fellow Canadian and famous karateka. He asked me later if I would like to see a really old sword art and I said sure, why not.

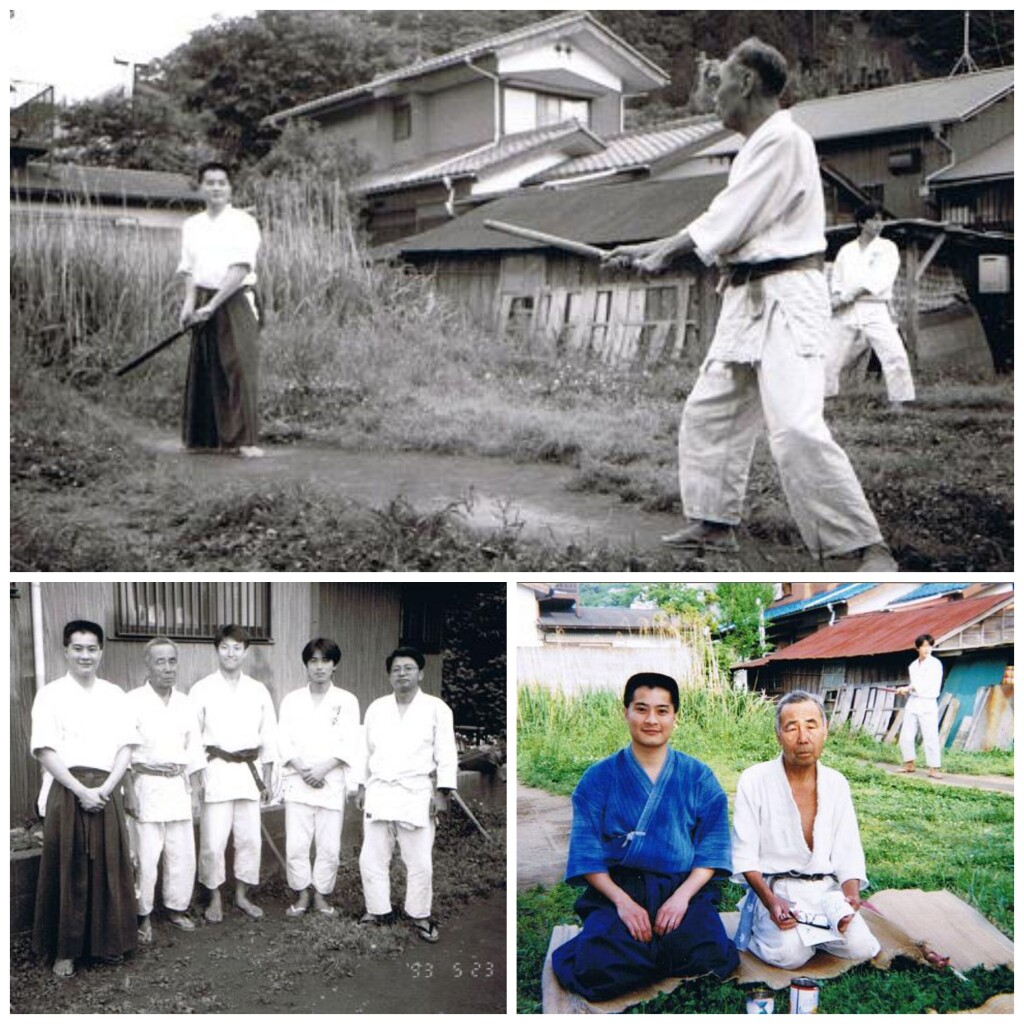

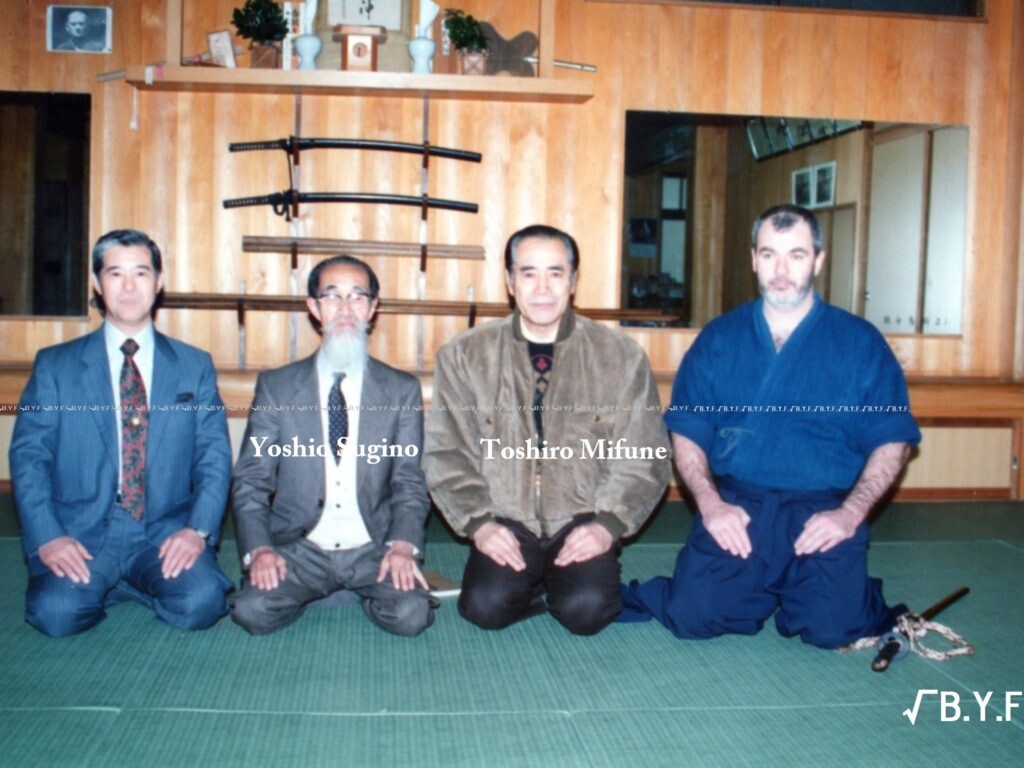

Tong Sensei at Sugino Dojo with his sempais: (left to right) Eri Kusano Sensei, Patrick McCarthy Sensei, and Sozen Kusano Sensei

The following Sunday, we arrived at Sugino dojo and as I stepped into the dojo, I was met by a little man with white hair and white beard (Yoshio Sugino Sensei actually). He was very polite and invited me in and showed me a chair. I really didn’t know what to expect but once the practice started, I was in awe. I felt as if I was in another time and place. It was exhilarating and awe-inspiring all at the same time. At times, I feel that it was a bit of destiny for this to have happened. Had I not been standing there on that platform at that precise moment when Pat walked by, I would never have met him and my life would have unfolded in a completely different way. That was destiny. Meeting Pat brought me to Sugino Sensei which then brought me to Mutoh Sensei, because they were friends, which eventually brought me to Kajitsuka Sensei. Destiny, I truly believe that.

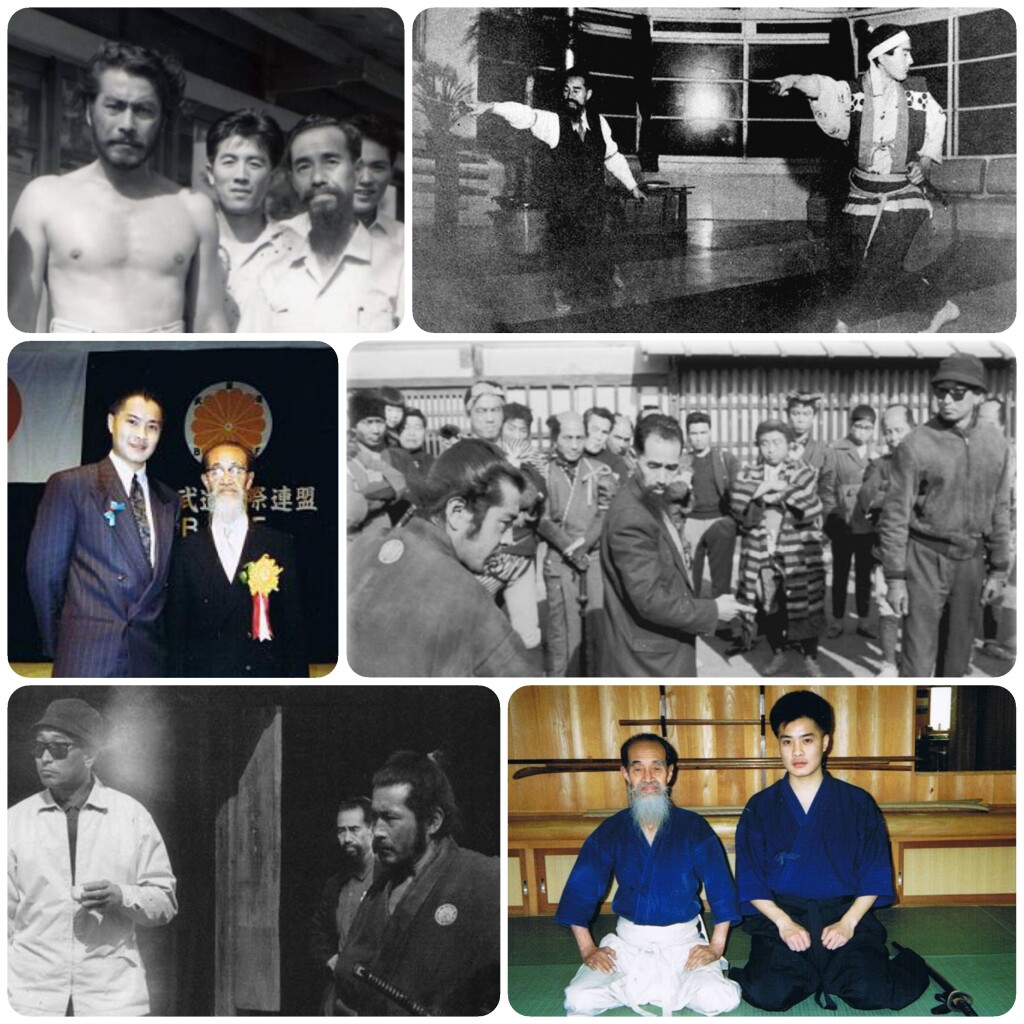

I have been incredibly fortunate to have studied under some great teachers. And maybe for your viewers, I should introduce who my teachers were. First off, my teacher in Katori Shinto-ryu was the famous Yoshio Sugino Sensei. He was the swordfight choreographer for Director Akira Kurosawa’s two most famous samurai films, Seven Samurai and Yojimbo, as well as for Director Hiroshi ingaki’s epic entitled Miyamoto Musashi in Japan, which was re-titled as Samurai Trilogy in North America. He was a budo superstar and he himself had the good fortune to have studied directly under Jigoro Kano, the Founder of judo, and Morihei Ueshiba, the Founder of Aikido.

Tong Sensei with Sugino Sensei

I also studied Ono-ha Itto-ryu under Master Takemi Sasamori, the 17th Generation Headmaster. Ono-ha Itto-ryu is the original swordfighting style that gave rise to kendo, the modern art of Japanese fencing. I had the unique opportunity to study this style through private one-on-one lessons with Sasamori Sensei and his son-in-law.

Tong Sensei with Sasamori Sensei

For iaido, I studied Muso Shinden Eishin-ryu iaido as a direct student of Master Toshihiko Izawa (7th dan kendo, 7th dan iaido). I was lucky to be a member of a small class of only 4 students, so I received very personalized instruction for many years directly from Izawa Sensei.

Tong Sensei with Izawa Sensei

And I studied Yagyu Shinkage-ryu under the distinguished Master Masao Mutoh, one of the foremost researchers of classical Japanese martial arts (koryu bujutsu). Yagyu Shinkage-ryu is arguably the most prestigious style of Japanese swordfighting, having been the official sword style of the Shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu.

Tong Sensei with Mutoh Sensei

And I now continue my studies under Mutoh Sensei’s successor, my eminent Master Yasushi Kajitsuka, the 11th Soke of Yagyu Shingan-ryu Taijutsu (Edo-Line) and 3rd Shihan of the Ohtsubo Branch of the Owari Line of Yagyu Shinkage-ryu. Master Kajitsuka is also the Secretary General of the Nihon Kobudo Shinkokai (the Society for the Promotion of Japanese Classical Martial Arts), the oldest and largest national association of the classical bujutsu (koryu) in Japan.

Tong Sensei with Kajitsuka Sensei

So I have been incredibly fortunate to learn under these excellent teachers. Really, I am just a product of them and their teachings.

———————————————————————————————————–

So in martial arts, just like in Japanese culture, there is a lot of bowing involved. How do you see that as different than what Westerners consider as bowing?

Well, this is a loaded question. Let’s take an example. Bowing. Some people equate this with submission, or ideas about subservience, inferiority, self-deprecation, or saying that you are below the other person. Like a sign of weakness. But it is not, at least not in Asian martial arts. I think with Western culture having been exposed to Asian martial arts since the 70’s, it is generally understood as a sign of respect. It is a form of greeting as well, like a handshake. But respect is a big thing. We see that now in America with the current protests. When respect is not given, then bad things happen. When you bow and the other person doesn’t, that’s not a good thing! And respect implies a bit of humility, which is a huge thing in Japanese martial arts. If you can’t stand the idea of humility, do not do Japanese martial arts. That should be the first lesson the student learns in a dojo. My first sword teacher, the famous Yoshio Sugino Sensei, said “Budo training begins with courtesy and ends with courtesy.” That is a very important first lesson. Courtesy, manners, respect, and humility. If there is only one thing that you take away from 20 years of budo study, this first lesson would be a great one that can serve you through life.

So where do we see some differences in culture? Right there at the beginning. The first thing you learn at the dojo is how to pay respects. Paying respect to the teachers, to your fellow students, to the Founder in some arts like aikido, or to a god like in some really ancient koryu. This is old school thinking. My first sword master, Sugino Sensei, said that ‘courtesy enters into technique. If you lose it (manners/politeness), you will become like a gangster, strong without brains (heart)’.

Deep down, bowing is about respect.

For the old school guys, even this simple thing is very important and cannot be overlooked. Why? Let me tell you a story. I was working with a student one day and we were working on a particularly complex technique, one where you need to have a good sense of control, blade control and point control. This student who fancied himself somewhat skilled was hitting my sword too hard and thus was having problems executing the technique properly.

This student was a physically big man and powerful. I suggested to him to take the power off. He did it one time but the next time, he went back to his preferred method. Naturally, he got increasingly frustrated. So I stopped the practice and asked him, “Why are you hitting with so much power?” He gave me a round-about answer. We practiced some more and tried the technique some more and still he was hitting with too much power. I questioned him some more, “So, if you agree with me that power in this instance is not a good thing, THEN WHY DO IT??” He mumbled some answer but I was undaunted and not about to be thrown off. I made my argument again and asked him again, more pointedly, “Obviously, it’s not logical. SO WHY DO IT??” Quite unexpectedly, he blurted out, “Because I want to!” I looked at him, “Why?” “To show him who’s boss!”

Remember that we are teaching some really deadly arts. In the wrong hands, it could be disastrous. That is why morality, ethics, manners, politeness, courtesy are so important. These are not hardcore technical skills like how to cut but they are important in their own right. So even there, there is a cultural difference and expectation.

So to the old school budo people, courtesy meant worshipping the gods, respecting people, revealing your heart, having a humble state of mind, having a thankful heart. That is the traditional Japanese budo spirit, they say. So this again is a little bit of a cultural difference.

———————————————————————————————————–

What about Rules? Are they Explicit (based on written rules) or Implicit (based on relationships)?

I found in Japan that a lot of rules were implicit (“you should know that”) and understood, and here is where we see Japanese culture at work. Things don’t need to be explained. That’s the way they have been socialized ever since kindergarten.

Another aspect Westerners found difficult is the idea of ‘haragei’ (‘communicating with your belly’). It is defined as “an exchange of thoughts and feelings that is implied in conversation, rather than explicitly stated. It is a form of rhetoric intended to express real intention and true meaning through implication”.

So sometimes things are expressed through a look, silence, changing of the subject, etc… Westerners feel the need to express themselves openly, to “clear up” things directly. But not so in Japan. Things are not said but understood. For example, here in the West, we would say “the message was communicated not so much in what he said, but more in what he did not say.” That kind of idea. It’s like a guessing game and kind of requires that you “be on the same wavelength” as the other person.

But there is the secret to interpersonal communication. Westerners seem to need to have the answers right now. And they would say things like “well, just say what’s on your mind.” In Japan, this is rude. Nothing is said directly. It’s like asking for a fight. Sometimes things are said indirectly, through nuance and innuendo. And Westerners find this frustrating.

———————————————————————————————————–

What about Making Decisions? Is it Democratic (by consensus) or Autocratic (hierarchical)?

Well, to start off with, a dojo is not a democracy. In all dojos that I have studied at, there is a clear pecking order, whether it is explicitly communicated or implicitly understood. There is a hierarchy and in Japan, it is not even questioned. However, you may think “I am in power now” and rule autocratically and sadly this is what happens with power. Absolute power corrupts absolutely, as they say. But there is another saying “With great power comes great responsibility.” and we must keep this in mind. And that is only if you care about your subordinates… or is it all about you? This is the great test of whether you are an enlightened leader. And here we see ego and also humility.

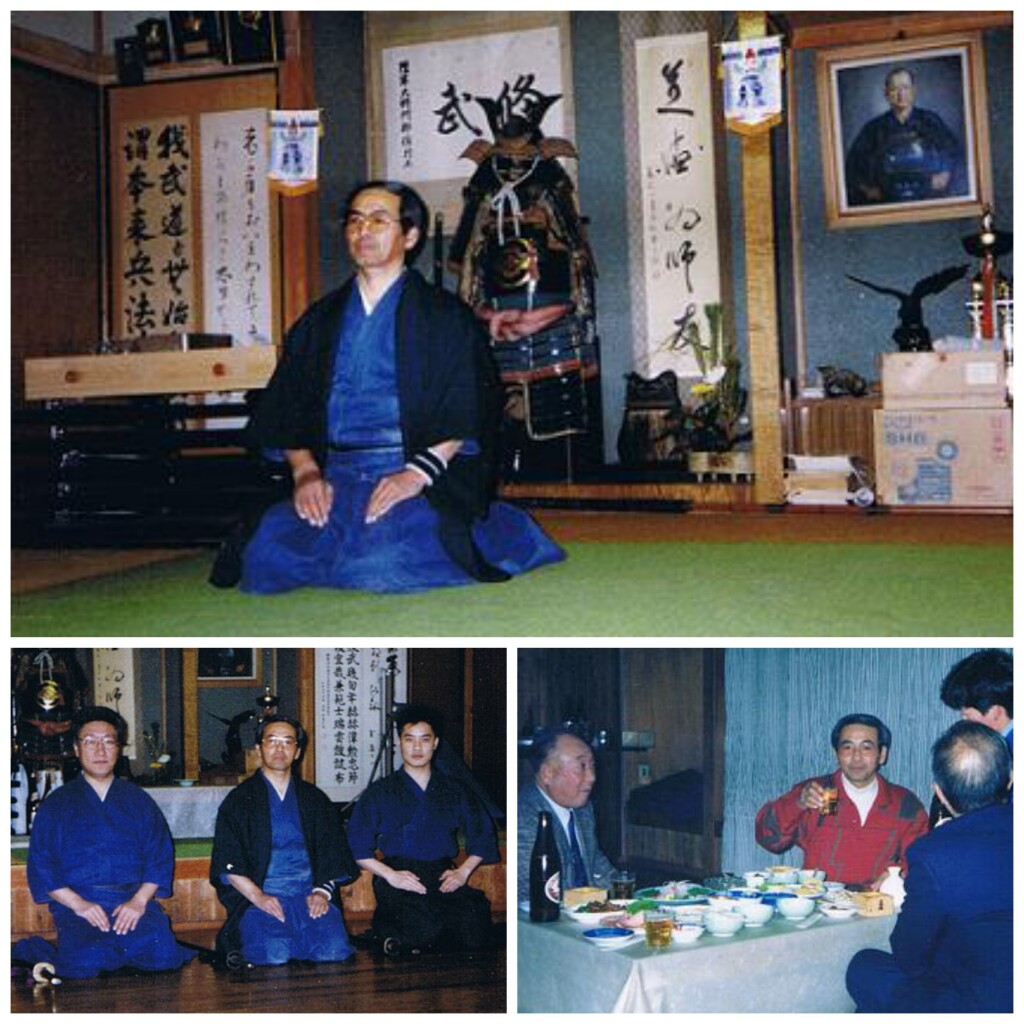

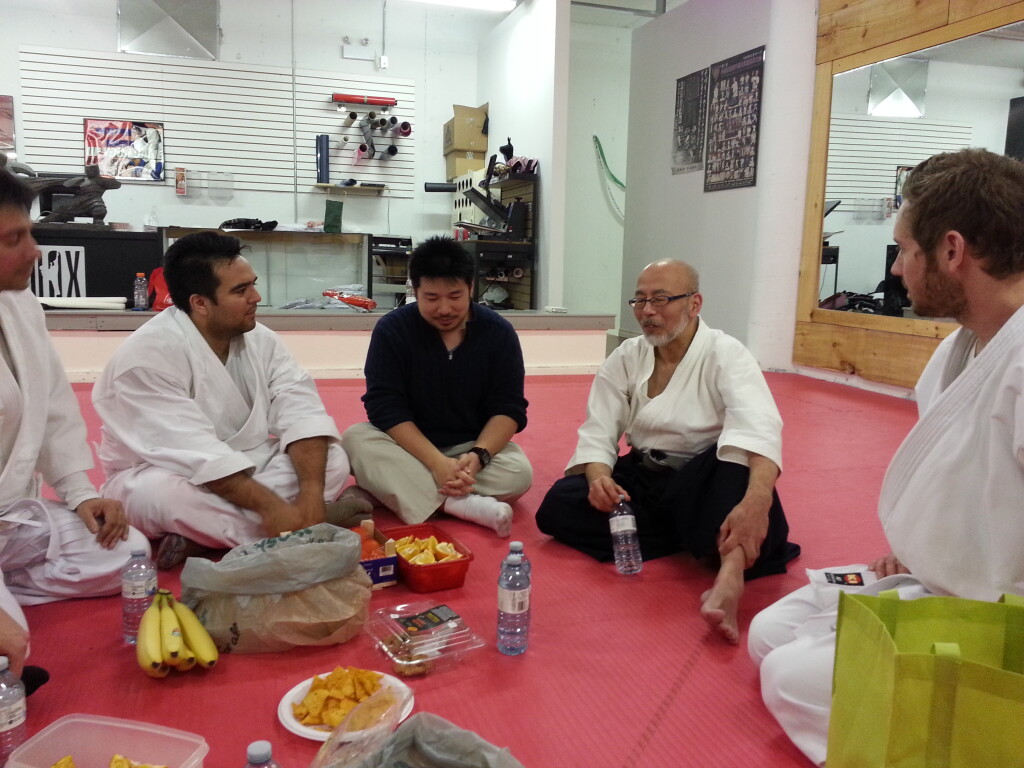

This brings up a good story from the 2015 seminar we had with my master, Kajitsuka Sensei. Someone had asked him about being the Soke (grandmaster or headmaster) of Yagyu Shingan Ryu Taijutsu and how it must be great to be at the top and decide things for everyone. It must feel great. To which he soberly replied that actually, in reality, he feels a great weight of responsibility. One of the students asked why. He said that he must be very careful with anything he does with the style and every decision. He said that he doesn’t want to go down in history as the person who screwed up the style. And here is the thing that we forget about someone in his position. He is the caretaker of the tradition, values, customs, philosophies and beliefs, and of course the techniques of the art. He said his job is to pass it down to the next leader, the next generation, correctly, and intact.

Kajitsuka Sensei answering questions about being the Soke (Grandmaster) in 2015

So rather than feeling like a king on a throne who can dispense favour or punishment arbitrarily and feel great about himself, he instead feels humbled having been given this great honour and also awed by the weight of responsibility attached to it, and is more determined to ensure that the style is taken care of and transmitted properly. I guess the closest analogy that comes to my mind is that of a priceless Ming vase. It’s great to be the possessor of it yet you have to take great care of it so that you don’t drop it and shatter it into a million pieces, and then the future generations don’t get the pleasure to experience its beauty. I don’t know if this is strictly a cultural difference in outlook about the exercise of power at the highest level but maybe in some ways it is as it deals with humility, which is a deep trait and characteristic of Japanese budo.

Kajitsuka Sensei with the Canadian Shingan Ryu Group in 2015

———————————————————————————————————–

“Cultural norms can serve as a template for expectations in a social group” — In a general sense, what does this mean? What are the pros and cons of meeting vs not meeting those expectations?

Well, a dojo is a social group. An association or a federation is a social group. And a social group is composed of members who share a common culture (standards, ideas, beliefs, ways of doing things, etc.). When you join a style, let’s say Yagyu Shinkage Ryu, or a kendo club, like at a university, you must learn the ways in which they do things, what they believe in, how they interact with each other. That’s the culture of the organization. If you don’t agree with it, you will leave. If you agree with it, you will stay. And there are expectations of how you are supposed to behave as a member of that group. Remember the old expression in Japan: “the nail that sticks up, gets hammered back down.” You must comply. And here is a bit of conflict with Western cultural ideas: like Madonna, Westerners want to express themselves. Or the other popular saying: “Be yourself.”

In the West, it is about ‘being yourself’

Well, in Japan, they think: “I want to be like others in my group. I want to blend in,” and “You don’t want to stick out in a crowd. You want to blend in.” Some people are okay with this and others can’t stand it. So now we have hit the nail on the head: it is all about groupness.

Being part of the group is the expectation

So back to your question, each social group, like a dojo or an association or a federation, has its own set of expectations on behaviour, values, and customs. And therein lies the potential conflict. You either follow them or you can leave. And in many cases, these expectations can be general cultural norms. In budo organizations, these can be traditional social norms as well. Here are some examples of conflicts. Sometimes it is your appearance, like tattoos, piercings, and so on, which are currently a fad in pop culture. Other times, it is your mindset: how you portray yourself on social media is another current example. So to answer your question, adhering to those expectations keeps you out of trouble. This is the idea of blending in and being like everyone else, not standing out, especially in a negative way. Not meeting those expectations sometimes can draw unwanted attention to yourself and can also negatively affect those who are associated with you. So in speaking of Japanese culture and their focus on the group and your part or membership in that group, here we can see how it is not about you but rather the group.

In Japan, it is about fitting in and doing what is expected

Here we see the conflict in cultural norms between East and West. Are you thinking of yourself and your own needs, or are you thinking of others? In Japanese culture, you need to think of others, the group. Before you do something, you think of the group. That is one big cultural difference between Japan and North America.

Here is a good example of the idea of the expectations of a social group. My master Kajitsuka Sensei is also the Secretary General of the Nihon Kobudo Shinkokai (the Society for the Promotion of Japanese Classical Martial Arts and Ways), the oldest national association of the classical styles (or ryuha) of Japanese budo and bujutsu in Japan (this encompasses what are known as the koryu). In 2015, I interviewed him about the Nihon Kobudo Shinkokai.

Kajitsuka Sensei (3rd from the left) representing the Board of Directors of the Nihon Kobudo Shinkokai

I asked him: “What is the mandate of the Nihon Kobudo Shinkokai? Its goals and purposes?”

He said: “The aim of our association is as follows:

1) To act for the preservation and promotion of Kobudo. The various arts that comprise “kobudo” are the traditional cultural assets of our country.

2) To assume responsibility for one part of the general idea of lifetime education and wellness. In other words, one of our goals is to contribute to the maintenance and enlightenment of good morals and manners in our country.

3) To contribute to the cultivation of our human character and human nature. We aim to contribute to the raising of our youth soundly and increasing the physical strength of our young people.

So even here, we can see that this huge association has certain norms and expectations.

They see the koryu as art forms and cultural assets. Therefore, their goal is to preserve these precious art forms. They are “cultural vessels”, vessels that contain the culture and traditions of their past. It is part of who they are, their national identity. We must never forget that. People forget this and get too wrapped up in “it’s a great art for killing” or “it’s the most effective killing art.” And that is what I meant earlier when I said that for a lot of Western teachers who have not been trained in Japan, or were not trained properly by their Japanese teachers here in the West, or else they ignored this aspect of the cultural teachings that their Japanese teachers were trying to teach them (this happens too because they do not understand the cultural aspect of budo or perhaps there was a language barrier), anyway, so that is what I meant when I said that some Western teachers focus only on the techniques, particularly the killing techniques. Some Western teachers that I know of were very young when they were instructed by their Japanese teachers. Of course, things happen and either their teacher passed away or moved away and they are left to carry on in the best way they can but were not thoroughly trained nor trained long enough. It happens. But this is sometimes the reason that they know only techniques. With young males particularly, they are initially attracted to the fighting aspect. So it is natural that they will focus on that. But that is only one side and without that cultural base, it is just empty techniques. Of course, it’s case-by-case, but here you can see some possible explanations of why this has happened here in the West.

The opening ceremony for the 75th Anniversary Festival of the Nihon Kobudo Shinkokai

Their goals are to educate people in good morals and manners. Isn’t that interesting? There it is again: for the Japanese, it is about manners. Japanese traditional budo is about manners, and this is according to this 800-member association representing all the “killing arts” of Japan.

And finally, another goal of theirs is to cultivate human character; in other words, like public education, their job is to raise good, productive citizens of society. It is not to produce killing machines, who can cut down as many enemies as possible. That idea has been twisted. The idea of budo is to raise good people, not “bad asses” as the current thinking goes. So there again, we have a cultural difference.

———————————————————————————————————–

How could we compare and contrast Social Culture vs Budo Culture — both for Japanese and Canadians?

Some old-school people think that budo is life itself, that budo equips you to deal with life. So in a sense, budo is culture. In this way, budo culture is social culture. The talk today is about the role of Japanese culture in traditional martial arts. I don’t think you can take culture out of martial arts. Let’s think about this. Your martial art, whatever it is, comes from a culture, be it Chinese, Japanese, whatever. Your iaido for instance comes from Japan. It didn’t come from India or France. It is a martial art born in Japan. That’s why they wear a hakama and not breeches. If culture didn’t matter, then you would wear breeches or some kung fu pants. But it does matter; it came from Japan. It also came from a certain time period. It didn’t come from 1980’s Tokyo. And it came from a certain social milieu with whatever thinking and customs were in vogue at that time in history and in that place where it was born.

Japanese budo comes from a certain time and place

So there it is: the cultural aspect of iaido. When you teach iaido, the student may ask: why are we wearing this funny skirt? Why am I sliding under a shelf or cutting the bushes and so on. Why do we have these strange words in a foreign language? Well, it’s Japanese. You see what I mean. That’s social culture. Or simply, that’s the culture of iaido. Culture is defined as “the customs, arts, social institutions, and achievements of a particular nation, people, or other social group.” Customs, traditions, social aspects, like thinking and beliefs. This is culture. Martial ‘arts’ are art forms, like painting is an art form. Art is an expression of a culture. So I believe that martial ‘arts’ are imbued with culture. I don’t know how you can teach a martial ‘art’ without discussing its culture: where, when, and how it came into being.

Ok, so what does this tell us now? Every martial art has its own culture and you have to realize what it is and follow that. That’s why for people who think, “Well, it’s just techniques.” I say, no, it’s not. For people who think, “Well, I’m just interested in the techniques.” Well, then why go to the trouble of spending so much time learning it? In this art of cutting like iaido or tameshigiri or battojutsu, there are not that many ways to cut a person. Eight different ways, some say. You don’t need much training to learn those. However, the richness of the art is in its culture. The samurai, Bushido, the Way of the Sword, the dress, the mannerisms, the way of thinking, and so on. That’s where the cool stuff is. The techniques? That’s just one part of it.

So you learn the eight ways to cut someone. The Chinese know this too. The Europeans also know this. So you learn them and then practice them for the rest of your life. So what makes it different than the others? What makes it unique and special, as compared to the others? It is that it is a Japanese art form. So there you have it. Automatically, it has become a cultural artifact; an art form from a specific culture. Is it different from the Chinese way to cut? Yes, it is. Is it different from the European way to cut? Yes, it is. And this is culture. You can’t take the culture out of it.

Some people will argue “But the Japanese sword itself is different. That affects the way they cut too!” Yes, but remember that the Japanese sword is also itself a cultural artifact, created in Japan according to Japanese swordsmithing philosophies of that time period. And because it cuts in a certain way, that affected the philosophies on how to cut with and how to swing that tool. But to explain that to a beginner, you will have to bring culture and history and tradition into the discussion. That’s my point. Whether you want to accept it or not, whether you agree with it or not, the fact remains. Japanese culture is an integral part of the art, whether it is kendo, iaido, or kenjutsu, or any of the myriad fighting arts of Japan like sojutsu, naginatajutsu, etc…

———————————————————————————————————–

What are effective ways to start learning a new culture? For example, Japanese people learning Canadian culture, and vice versa Canadians learning Japanese culture.

I think it starts with listening. You’d be surprised how many people don’t really listen. They can hear things but listening demands a different kind of skill and a mindset. Are you really ready to learn? And that starts with listening. Not just listening with your ears but listening with your heart.

Second, you have to have some interest in that new culture. Well, this is a really important point. Are you truly interested in that culture?

———————————————————————————————————–

What are easy challenges to overcome?

I don’t think there is ‘an easy challenge’. However, nowadays, with the world all interconnected and feeling like a much smaller place, it is easy to get access to Japanese culture. On the internet, YouTube, etc. you can find anything Japanese (movies, music, anime, and others) if you care to search for it. In the larger urban centers, you can find Japanese communities, like the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre (the JCCC) here in Toronto. They put on cultural activities, celebrations, and you can find language courses and classes in the traditional arts. So it is possible to get exposure nowadays to Japanese culture.

JCCC has many classes in Japanese culture

———————————————————————————————————–

What are difficult challenges to overcome?

Being closed minded. Feeling threatened. And that’s natural. Because we are scared. Fear is a big thing. Like George Lucas said, quoting Buddhist aphorisms: Fear leads to hatred. Some people believe that to embrace something new, I have to completely discard my previous learning. And herein lies the problem: black and white thinking. It’s either this or that. Why not have both? It’s like an ultimatum. You must choose this one or that one. Why? Why so extreme?

When people have a fragile ego, then they are scared when anything threatens that safe bubble that their identity is wrapped up in. I am happy with my world, my own little bubble. To go outside that safe bubble, to really go exploring the vastness is scary. You’re not sure who you are anymore. “I’m going to lose my values.” No, you’re not. But why not try some new values?

As a practical example, when people first join our style from another style, they are afraid. And the longer they had studied that other style, the more resistant they are to change. In some cases, they physically cannot. But in a lot of cases, it is mental. So I like to say, open a new file folder. I am not erasing your previous learning, but let’s add a new file folder to your existing file folders. If you are really skilled, you can handle multiple file folders. Those are the budo superstars. They can manage it and not have any compunctions about it. They are like “Yes, give me more. I want to learn more!” They are more open-minded, like a child. This is like “Shoshin” (beginner’s mind).

If you can only do one thing, some might consider this good. Others might consider you a “one-trick pony.” In the first sword style I learned, Katori Shinto Ryu which is a battlefield style, if you can only use your sword, you will have a short life indeed! In that style, you are trained to be a Master-At-Arms who can use many weapons. On the battlefield, when you lose your sword or it breaks, you need to pick up anything off the ground and use it, whether it is a staff, a naginata, a spear, etc… So this teaches you to be multi-adaptable. Breadth of knowledge and skill.

There is something to be said for people who know one thing very well. There is also something to be said for people who are well-rounded. If you are both, you are the budo superstar.

There is also the delusion of being open-minded. Some people see Japanese culture and say, well we’re not so different. We do the same things, we eat the same way, we think the same basic ways, and so on. So they view Japanese culture through the lens of Western culture. In other words, they are still reluctant, deep down, to embrace something new.

Because to do that, to start down a new path is to become a beginner again. Everyone wants to feel like they have a good grasp of what they know. You would have to go back to knowing nothing. That’s scary. And it gets worse as you get older. Ego is wrapped up in that. Control is wrapped up in that. As older adults, we think we know it all, we’ve seen it all. Our ego is wrapped up in that: knowing our world. Learning a new culture is learning a whole new world, making many mistakes, feeling inadequate and clumsy. Feeling foolish. And usually by a certain age, older adults have built up a social status, a position in their world, from which they cannot come down. They can’t become a beginner again. It would be too much of a drop in status that they cannot tolerate. That’s ego. Ego gets in the way.

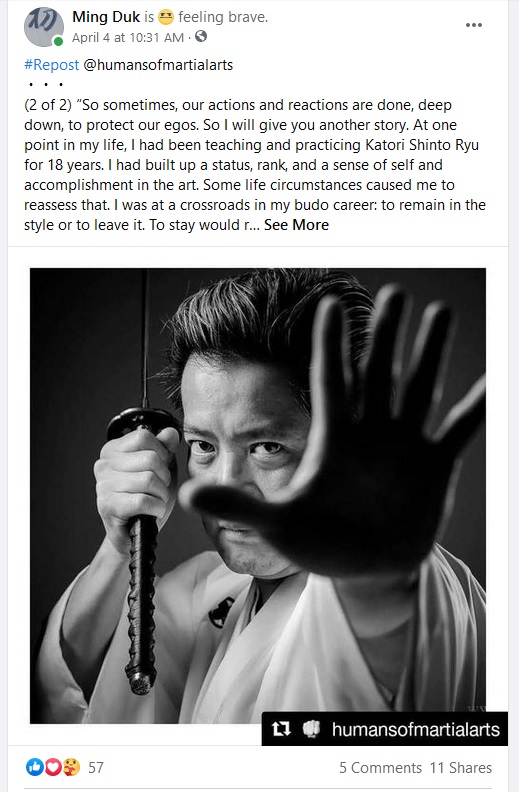

So sometimes, our actions and reactions are done, deep down, to protect our egos. So I will give you another story. At one point in time in my life, I had been teaching Katori Shinto Ryu for 14 years and practicing it for 18 years. And by this amount of time, I had built up a status, rank, and a sense of self and accomplishment in the art. Some life experiences and circumstances caused me to have to reassess that. I won’t go into the reasons but I was at a crossroads in my budo career: to remain in the style or to leave it. To stay would require that I change a lot of the things I had been doing, to adapt to a new way of doing things in this art which I was very familiar with. That’s hard to do. On the other hand, to go in a very different direction with a new style would require that I become a total beginner again. Again, another hard thing to do. Most people would rather stick it out, keep their rank, their privileges, their status. To go in a new direction, to embrace something completely new and totally unknown, is scary, because you have to really become a beginner again. And I have to admit, ego was involved in that decision-making process. My ego and pride were saying “stay”. But I took a leap of faith. And jumped into the unknown. It was scary and totally liberating. Sometimes new is good.

Here’s another story. When I interviewed my master, Kajitsuka Sensei in 2008, I asked him: “As a teacher, what do you try to teach your students, apart from just technique?” He gave three rules.

“1. Love what you do. This is the most important.

2. Do it from the heart. We say “kokoro”. In other words, do it with all your heart and soul.

3. Continue it. Keep doing it. Don’t stop.

Then he said: “These are the three main rules. Now after these three, I also recommend to my students two more:

4. Don’t be afraid.

5. Take things on. By this, I mean, try new things.”

Yes, I love that. Don’t be afraid. He is totally right. Fear stops us from trying new things, embracing new ideas. And yes, try new things. You never know. It may totally change your life…

So these things are mostly mental and psychological things but they are, as you said, difficult things to overcome. And like we see in our style of Yagyu Shinkage Ryu, these mental barriers, which are rooted in ego, stop us from accomplishing things.

———————————————————————————————————–

Is there a time where it’s better to just accept without understanding? What does it mean to understand culture, or is it all taken on faith that comes from an individual’s upbringing?

If you truly trust the teacher. That is why choosing the right teacher for you is extremely important. Not the teacher who is around the corner, the convenient choice. But doing your research, talking to people, meeting people, and then going and finding the right teacher.

This brings to my mind a personal story. We had to go back to Japan in 2008 for my mother-in-law’s funeral and I visited the old dojos to pay my respects. And at that time, I was in the midst of re-evaluating what I wanted in my life, where I wanted to go with this next stage of my budo life. I wasn’t 20 years old anymore. The things I needed in my mid-20’s were not the things I needed in my mid-40’s. After I met Kajitsuka Sensei, I knew right then and there, intuitively, that he was the teacher for me. It was good luck that I met him. Some might call it destiny. But it wasn’t going to be an easy path. He was way over in Japan. I am in Canada. It doesn’t matter. A couple of days with him is worth more than having many years with an inferior teacher.

And nowadays, there are more ways to learn than just being there in the dojo. You don’t need to be at the dojo all the time to learn. I remember at the dojos where I studied in Japan, there were students who had been there for years and years and didn’t seem to have learned much or progress much. And then there are other students who are there for only a short period of time but they gain a lifetime’s worth of knowledge and skill. It depends.

I understand how 99% of the people would just go and practice with the teacher around the corner. That makes sense too. But for some people, the special 1% who are extremely serious about their budo, there is no comparison. These types of serious skilled budoka will not be satisfied and will go and find the right teacher. It actually brings to mind a little story about my father-in-law in Japan. He is the president of his own company. My wife noticed that he frequently dined at restaurants which had a reputation for excellent food. She asked him one day, “Why do you keep eating at these expensive places?” To which he replied, “I am getting too old to waste my time eating junk.” You know what? I am coming around to understanding his point. Find the right teacher.

About your question about where it might be better to accept without understanding, I would say that sometimes you might not be ready to understand it just yet at your level of development. Accept the lesson. Absorb everything like a sponge. Mull it over. Sometimes, things I learned years ago suddenly become clear, like an epiphany. So the key is to pay attention, like really pay attention when the teacher is talking. Sometimes we take things for granted, like thinking that our teacher will be around for a long time. That would be fantastic, in a perfect world. But you never know. It might be the last conversation you have with your teacher. So you have to treat each meeting as a precious event.

Anyways, sometimes you won’t understand at that moment but pay attention and remember it or even better, write it down. Years later, it will make sense. Happens to me all the time when I read books.

But all this discussion really centers around “readiness”. Ready to learn new things about culture, ready to learn new techniques, ready to learn new ways of thinking, ready to learn new belief systems and value systems. You may be ready, you may not. Like in my own case. Sometimes my masters will teach me something. Even if I am not ready to comprehend it, I am listening and I am absorbing. Like I said before, it depends on being ready to listen. Listening with an open mind, as they say “with your heart open”; listening with your heart, not just the words but the spirit of what the teacher is trying to teach you or tell you. And I also mentioned about being interested in that new thing: culture, mindset, beliefs. That’s important too. If you’re not interested, genuinely interested, you will shut it down and dismiss it. Chiefly because it goes against what you believe in. So those two barriers to learning are important. So the question remains: are you really ready to learn?

You mentioned faith. Yes, faith is very important. If you trust the teacher, you put yourself in their hands. As Sugino Sensei said, “Teaching in traditional budo is from the teacher to the student, heart to heart, without words.” That special kind of relationship is the key. That is really taking “a leap of faith.”

“Teaching in traditional budo is from the teacher to the student, heart to heart, without words.”

And don’t worry, budo is imbued with culture. If you are receptive (remember, being ready to learn), you will absorb culture from your teacher. So that is why finding the right teacher is the most important thing.

———————————————————————————————————–

What fundamentals human traits (e.g. openness vs closed-mindedness) are necessary to start this learning?

Yes, open-mindedness is the key. Do you really want to learn something new? Really and truly? Are you willing to let go of preconceived ideas and really take in something new, radically different? It all comes down to change. Are you willing to change? That is a deep fundamental question.

Kajitsuka Sensei said: “Budo has survived by adapting to each era. To continue to survive, it has to adapt and keep adapting. All styles that stopped adapting, have died out. The Edo Line of Yagyu is no more, unfortunately. This is a prime example.”

Let me give you my personal example of first arriving in Japan. I remember arriving at Narita airport. And being met by the company representative and bowing; my first taste of a different culture. I remember riding the shuttle bus from the airport to the company dormitory. I was looking out the bus and I saw some young men in a car, with their feet sticking out the window and wearing flip flops. How utterly strange and alien a place it was. A beach culture, an island mentality. I remember arriving at my apartment. It was tiny, what they call a 2DK: one tiny bedroom and a living room and a kitchen; that’s it. But this was typical for a small family of 3 or 4 to live in. That was a culture shock; I was used to sprawling bungalows with a big front yard and an endless backyard. They had prepared it for me with a welcome basket with some Japanese bread. I remember thinking, “Wow, their bread is sliced so thick”, like an inch and a half. Even such a simple thing was so different. This really tests how open-minded you can be. Either adapt or go home. I was now scared. It really hit me hard in this first truly private moment I had alone and to myself; that I was thousands of miles from home. I was really and truly on my own, in a strange country, halfway around the world. I was all alone. And no one spoke any English. I was so petrified. I didn’t want to leave my little apartment because I would have to face this new, strange society where everyone speaks in some alien tongue. I can’t communicate. I don’t know what they’re saying. They don’t know what I’m saying. What am I going to say when they ask me a question and I don’t understand what they are saying? All those things that you take for granted in your own culture, that you don’t even think about, aren’t there anymore. And you feel lost and scared and utterly alone. So I had to adapt. I had to be brave and step out that door.

Here’s another thing that Kajitsuka Sensei said: “Our fundamental philosophy is to adapt and change. “Adapting” is a better word. It means adding to, modifying, to fit new situations and circumstances. If you don’t adapt, if you just change, then you become like mixed martial arts. Replacing something with something different. You lose the original meaning, the original purpose, and the original spirit of budo.”

Here he talks about the spirit of budo. That spirit is about social norms, beliefs, values. That is culture. And what are those values? Perseverance, adaptability, open-mindedness, change. Many people think that budo is just about fighting. But it’s not. In the old days, it was called ‘hyoho’. It included the art of war but it also included things like how you eat, how you rest, how you dress, etc.. All sorts of mannerisms or behaviours. Even hygiene and health were important. In old school budo thinking, living a healthy lifestyle is essential because it resulted in developing a healthy body. A healthy body resulted in a healthy mind (having clarity of mind). A healthy mind resulted in healthy technique; technique that is clean, crisp, and precise. Not muddled. And this idea extended to the dojo, keeping the dojo clean. And also extended to your clothes, keeping your clothes clean and taking care of them. Taking care of yourself and your body, eating right, getting enough rest, taking care of your clothes, taking care of your dojo. It’s all related. That is hyoho. Budo in this way is, yes, truly a way of living life and a way of approaching life, to keep you safe, and to develop vitality (in Japanese, they call it ‘seiryoku’), physical strength (tairyoku ousei), and energy (kiryoku). Without these, you won’t have the energy or strength to live or to fight or to do your duty, your work.

So to answer your question, yes, openness, being open-minded is very important. Being willing to change is also very important. Change is difficult, I know. So you kind of have to be a little adventurous. And of course, wanting to learn more is the starting point.

__________________________________________________

Inside Look Podcast 012 – Douglas Tong (Yagyu Shinkage Ryu) Canada

Introduction

Today, we’re speaking once again with Douglas Tong Sensei from Orangeville, Canada, as we continue our exploration into Japanese culture in budo.

Part 2 of this series will focus on the concept of rank, and where it fits within Japanese martial arts, and the broader society.

In this stimulating lecture, he shares insights from his Sensei as well as personal experience and knowledge from a lifetime in education, including a graduate degree and a career that spans decades.

So without further ado, I give you, Douglas Tong Sensei.

———————————————————————————————————–

Where does cultural learning fit within a martial arts curriculum? What should be implicit (e.g. where we stand in the dojo) vs explicit (e.g. lectures, notes, or discussions about culture)?

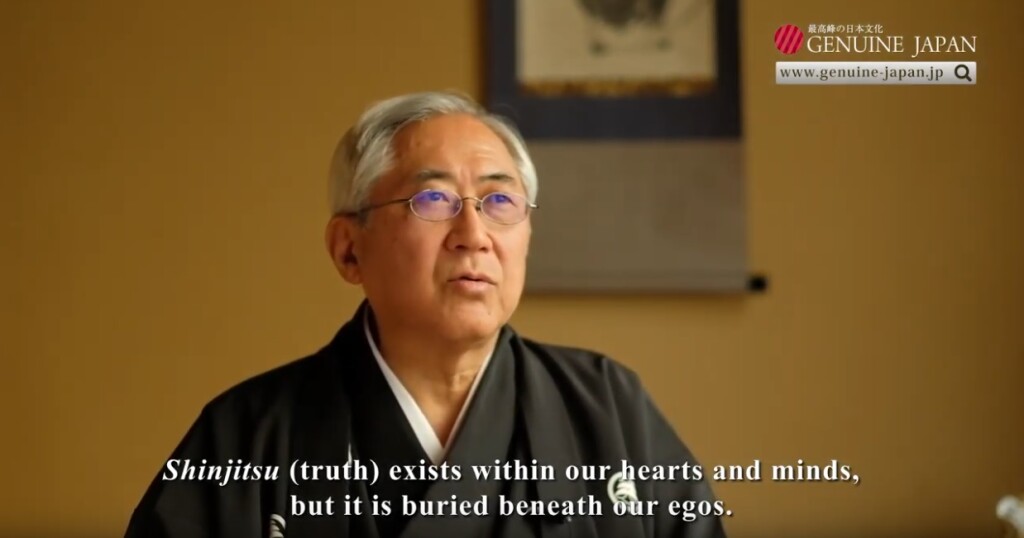

Where does cultural learning fit? Well, you can’t just teach technique after technique, like what’s the best way to cut someone or fancy ways to block someone’s cut, and so on. That’s empty. Like I said just now, it’s all related. To the old school guys, budo is a way of life. Here, in the West, particularly with teachers who were only trained in the West, it is all about techniques. And more precisely they seem to really like techniques that kill. Maybe they consider that cool. This brings to mind the seminar we had in 2016 with Kajitsuka Sensei where he taught about Yagyu Shingan Ryu Taijutsu, which is a sogo-bujutsu, a composite art but is best known for its excellent jujutsu techniques. He said that Yagyu Shingan Ryu is really a very complete art, with two sides. What the students now focus on is only one side of the art, that of the destructive side of the art. Students focus on how to harm or hurt another person, using pressure points and knowledge of the body’s weaknesses and critical breaking points. So, what they study now is incomplete. There is a constructive, more beneficial side of the art which has been partially lost. That side embraces healing, like using these same pressure points and knowledge of the body’s energy centers and ki (or ‘chi’ in Chinese medicine), to help make people feel better like reiki and shiatsu among others. As Kajitsuka Sensei explained, this art can be used to hurt, to destroy. But it also teaches how to heal a person, to help people feel better. Budo is not just about how to kill someone. That’s empty and a little soul-destroying. You need some deeper understanding to balance out that kind of one-sided perspective. Granted, I am sure that there are some styles that don’t care about the opponent; they are only interested in killing people or in fighting. But in arts like Yagyu Shinkage Ryu which we study, which is known as the Shogun’s style, killing off your population is not a good way to build up the country. Also, Yagyu Shinkage Ryu was built on Zen Buddhism which espouses compassion and not killing your fellow man. The fundamental philosophy in Yagyu Shinkage Ryu is ‘The Life-Giving Sword’ with all its shades of meaning. Yagyu Munenori said that we don’t kill the person but rather the evil he is about to commit. To stop his evil, we have to stop him somehow, but that does not necessarily mean by cutting his head in two.

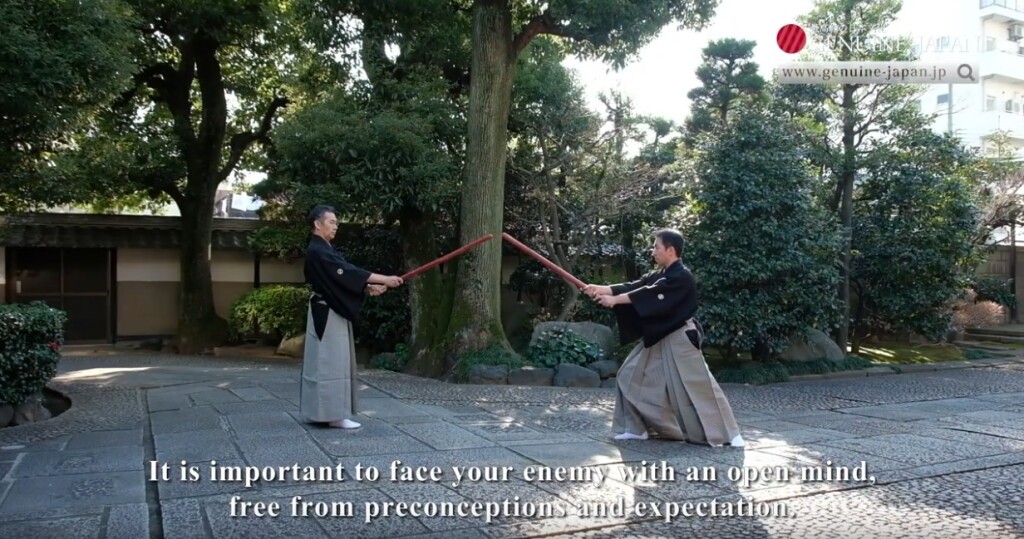

There are many ways to stop someone that don’t even involve using a sword! Like in Yagyu Shinkage Ryu, we have the famous idea of ‘muto-dori’: how to fight bare-handed against an opponent who has a sword. Now, that is scary! Try doing that! But it is one of our highest principles. That is ‘Hyoho’. Some people just translate ‘hyoho’ easily as “the art of war”. But is it only an art of war? Maybe we should change the wording in that definition of ‘muto-dori’ to: how to “survive” bare-handed against an opponent who has a sword. That changes your whole perspective. Now it is not just an ‘art of war’ but rather an ‘art of life’. Now, we are talking about belief systems, philosophies, values, ways that we see the world and how to act in it. Now, this new definition brings in missing pieces like morals and ethics. You need them too. Like Kajitsuka Sensei said in my interview with him, “With the Edo Period and the new Shogun, the sword became not about killing people. It became about promoting life. The sword became the way to grow a soul.” True old-school budo is about how to live your life. Yagyu Shinkage Ryu, as the Shogun’s style, played a pivotal role in the new era of peace at the beginning of the Edo Period. That’s when and where it really gained prominence. So things like this, where you delve into philosophy, values, beliefs, these are the ‘culture’ of the style.

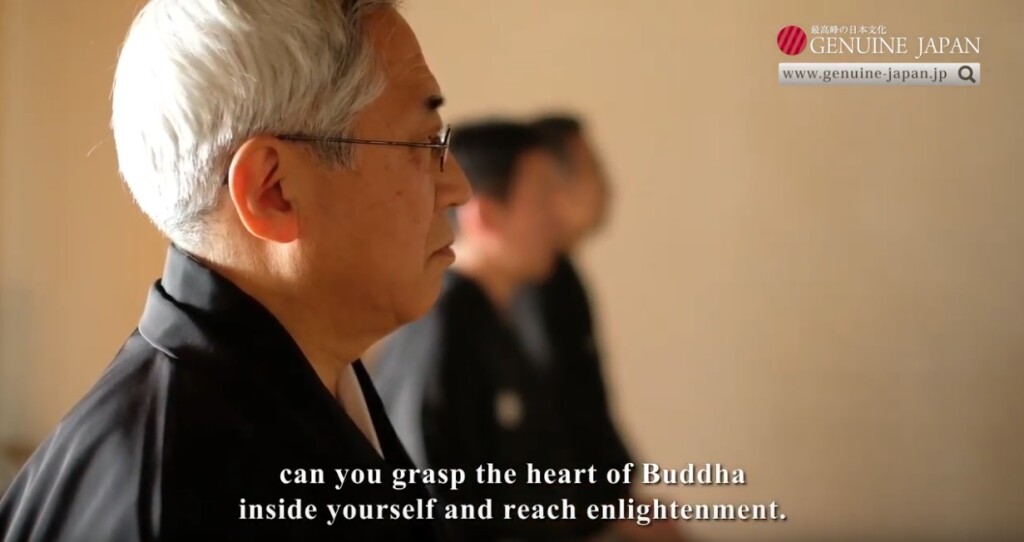

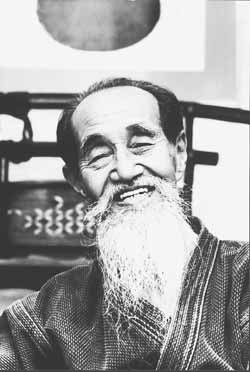

I am sorry but I will now have to talk a bit about the style that I study which is Yagyu Shinkage Ryu in order to give you a concrete example of what I mean. The reason is because it is an old style, a koryu. And because it is an ancient style, it is deeply rooted in spirituality and this is a form of cultural learning, as spirituality and spiritual beliefs of a country or society are, yes, part of their cultural thinking. The question today is: how does cultural learning fit within a martial arts curriculum? Well, in this ancient style, it is an integral part of the curriculum. In a recent documentary with Yagyu Koichi Sensei (the Soke of Yagyu Shinkage Ryu), they asked him: “what is the essence of Yagyu Shinkage Ryu”? He answered: “It is Zen”. He went on further to say that in the fundamental philosophy of Zen, when you pursue the essential qualities within yourself, you can grasp the heart of Buddha inside yourself and reach enlightenment.

The spirit of Shinkage-ryu is Zen

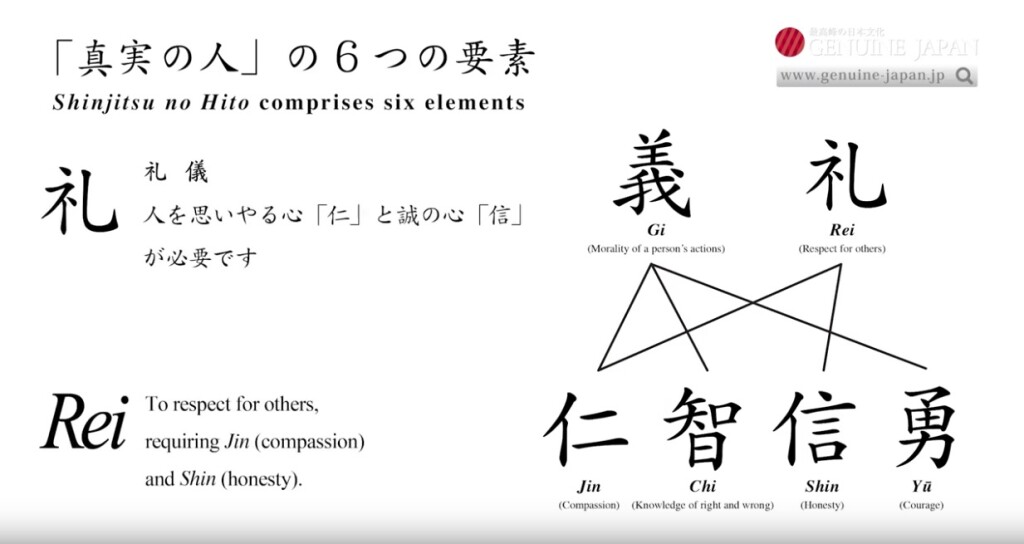

So in our school, we try to attain this state, which he called “Shinjutsu no Hito” or “Person of Truth”. And this ideal consists of 6 elements: Gi (morality), Rei (respect for others), Chi (knowledge of right and wrong), Jin (compassion), Shin (honesty) and Yu (bravery or courage). So, again, they are: Morality, Respect, Justice, Compassion, Honesty, and Courage. These virtues are what is known as ‘the morality of budo’ or in Japanese “butoku”, and they are actually derived from the 5 Confucian virtues. Anyway, Yagyu Koichi Sensei said that this ‘shinjutsu’ (this ‘truth’) exists in our hearts and minds but it is buried beneath our egos. Ah, so here we run into the idea of ego again. So, our school emphasizes finding and accepting this Shinjutsu no Hito, which is the real essence of self.

The Concept of ‘Shinjutsu no Hito’ (“The Person of Truth”)

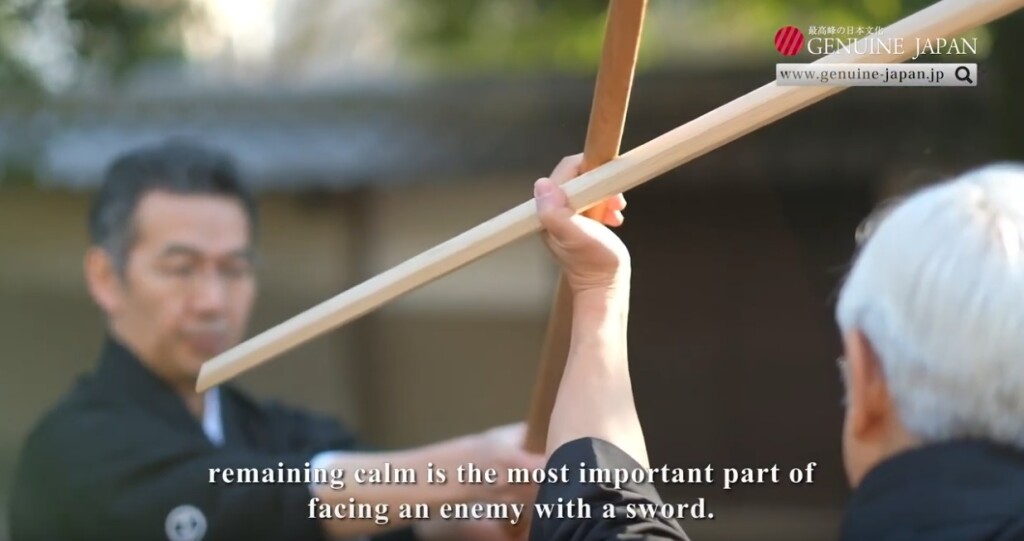

Now you may wonder why? What significance does this have in our art of swordsmanship? For samurai, remaining calm is the most important part of facing an enemy. He said whenever you face a life or death crisis, if you cannot calmly assess the situation, you will not survive. To find this inner calm, that is where Zen and its fundamental philosophy of attaining truth within ourselves (which means seeing clearly without preconceptions and ego-clouded perspectives) and grasping the heart of Buddha (which means attaining that calm, unperturbed sense of being) is ultimately useful and effective. So you can see here how cultural learning, in this case based on Japanese religion, is infused in our study of martial arts.

The essence of this school: remaining calm in times of crisis

You may question “but that is religion; it is not culture.” But you have to remember that in the ancient days, culture was largely based on religion. In the Middle Ages, there was no state-sponsored education. That I believe came later toward the end of the Edo Period. Essentially, you worked in the fields. The only educated people were the monks and the nobles. Education existed in the monasteries. And the rich, the nobility, hired their own tutors. Everyone else was uneducated. And in the monasteries, the education was largely based on religion: reading and writing the sutras, documentation of stories, etc.

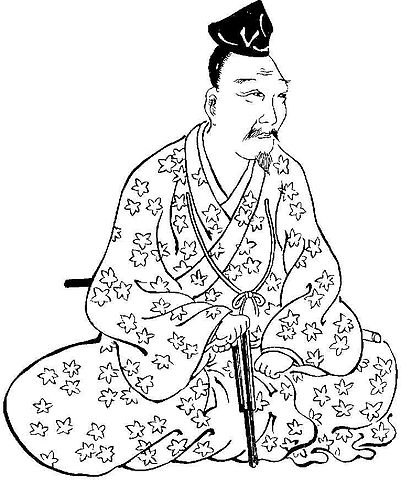

Here’s another example. The first sword style I studied is officially called “Tenshin Shoden Katori Shinto Ryu”. It means “Heavenly True, Correctly Transmitted Style of the Way of the God of Katori”. Already, there is religion in its title. It was created in the mid-1400’s during the Civil War period called the Sengoku Jidai when there was anarchy as warlords competed to gain control of the country. According to the legend, the Founder Choisai Ienao was visited by a god one night.

Iizasa Chōisai Ienao, the founder of Tenshin Shōden Katori Shintō-ryū

The god gave him the divine scroll and said to him: “Later, you will be the teacher of every sword.” Which kind of became true, as Katori Shinto Ryu came to influence and seed many later styles. In fact, Yagyu Shinkage Ryu came from a fusion of Katori Shinto Ryu with Kage Ryu, to become “Shin-kage Ryu”; in other words, the ”New Kage Ryu”. Anyways, eventually with more training, Choisai uncovered ‘the secret of the unification of man and god’ and then he ‘unlocked the secret of the Warrior’s Law’ (in other words, heiho). It was truly a ‘gift from the gods’. Well, so there we see the strong role that religion played in this style. In Katori Shinto Ryu, they pray to a Shinto God Futsunushi-no-Mikoto, the god of war and the patron deity of the Katori Shrine.

Futsunushi-no-Mikoto, the god of war and the patron deity of the Katori Shrine

And they also pray to Marishiten, the Buddhist goddess of light, who is the guardian deity of the samurai, the warrior class.

Marishiten, the Buddhist goddess of light, and the guardian deity of the samurai

Katori Shinto Ryu is connected to the Katori Shrine, a place of religion and worship. So this style’s history and traditions and beliefs are very heavily based on religion. This is its culture. That’s where it came from and you can’t take that cultural aspect out of it. So to people who say, “Well, I’m just interested in the techniques,” they are missing the whole rich heritage of the style. Why is heritage so important? Heritage is important because it helps us to understand the history and traditions, enables us to develop an awareness about the art, why we are the way we are, why we believe the things we believe. In a martial art, it tells us why we move the way we move, why we cut the way we cut, and so on. Heritage is a keystone of the culture of the style or art, and it plays an important role in the world view of its practitioners.

The Katori Shrine is a Shintō shrine in the city of Katori in Chiba Prefecture, Japan

———————————————————————————————————–

Let’s talk about rank. What does it mean for the individual vs for the organization?

First off, for the organization, we need to define that. If we are talking about an individual dojo, rank on this smaller scale helps to define everyone, their relationship to everyone else there, and their level of progress and accomplishment in the art. In some situations, it defines whether a person can teach that art. In your art of iaido for instance, reaching a certain rank gives a person the authority to teach. Now, whether the person has the knowledge and skill to teach once they reach that rank is another matter and another discussion point for another time. Why? Because teaching is its own separate art form. You may have all the knowledge in the world but not be able to teach it, because teaching is the art of ‘reaching’ students, not just transmitting content.

Anyways, to get back to the topic, if we are talking about a larger organization like an association or a federation, those kinds of large bodies need a ranking structure to keep track of everyone. It’s an operational necessity. In large federations, you need a system to organize your teachers and your students and a hierarchy to maintain control. So ranking is a logistical necessity. In this situation, rank then becomes very important. For this large kind of organization to continue to survive, it needs a system to promote people, particularly into the teaching ranks so that they can teach the people coming in, like a big machine. This perpetuates the system. People will leave the system (they pass on, they drop out, and so on) and new people will come into the system. Someone needs to educate the new people coming in. Is it a good thing? Well, I would rather consider it a necessity. Whether it is good or bad depends on how the people involved use it.

A ranking system also allows the breaking up of the curriculum into pieces (or levels or sections), to make the learning of the curriculum easier, breaking it down into digestible chunks that the students can handle. It also gives the students clearly defined goals to achieve and strive for. It basically answers the question: what is a student supposed to be learning at a certain level? So in this way, it is a logical structure.

Now, as regards the people, how does rank affect individual people? Well, on a positive note, it is a clearly defined system: you know exactly what you have to do to achieve the next rank. It gives the students a yardstick by which they can measure their own progress, so they know how they have done, how they are doing currently, and what they need to do to keep progressing. It’s a measuring stick. The students feel a sense of accomplishment and can clearly see a roadmap for learning.

Having a ranking system also necessitates that you have a testing structure in place. To get to the next rank, you need to undergo a test. In big organizations, these tests take on a standardized nature so that each student does the same test to ensure consistency. So, here we see the necessity for a set of agreed upon standards for proficiency at a certain level in the art. On the surface, these kinds of standardized tests also give the impression that there is an objective measure. This in theory allows equal opportunity for all students for advancement without bias or favouritism. In theory, it sounds sensible and fair. A standardized test will look at your technical ability, whether you can perform what is required. It will also look at your knowledge of concepts and principles. These are things that can be quantified and measured objectively. In theory, a student from Vancouver is just as able to pass the test as a student from Toronto or Montreal. So for many people, this is a good thing. It creates a level playing field.

That having been said, rank does also present a danger: The more rank that is involved, the more danger of people developing a sense of and becoming dominated by their ego and pride. This is not due to the system itself but how the people involved use or abuse the system.

I do not want to focus on negative things but I have heard that the rank system can sometimes bring with it a whole host of issues involving hierarchy, power politics, exclusion, ambition, ladder climbing, clan mentality and the formation of cliques, the evolution of a caste-like atmosphere, back-stabbing, and other typical social issues that we see in large organizations and corporations. In this kind of scenario, it is not good for the individuals involved nor is it good for the organization as a whole, as there is no cohesion or unity. Like any corporate organization, it can become very dysfunctional. And it can hurt people who are involved.

And this is when focus on the art comes to be forgotten. The people are too busy climbing the ladder or all their energy is wasted on keeping track of everyone else and all the gossip. So in some cases, they view learning the art merely as an act of learning only what they need to, in order to pass the test, so that they can reach the next rank or level. That is when the beauty of the art gets forgotten. It becomes purely a technical exercise. I suppose it is kind of like how some people approach post-secondary studies; you can approach it from a love of learning perspective, where you are interested in learning about that field, or you can view it in more utilitarian ways as a means to an end, which is to get a job. They don’t really care that much about the subject they are studying; they care only about what it can get them, which is namely a job (which equates to money and status). So these are some ways in which having a ranking system can have not so positive results. But it depends on the person, or the people involved. The ranking system is not at fault, it is just a system. It’s how people view the system and interpret the system and use the system for their own purposes.

Which reminds me of a story. My old master, Sugino Sensei, asked me one day if I wanted to test for my shodan (first degree black belt). I said that I wasn’t interested, politely of course. I was young and idealistic. Maybe I should have but I didn’t really care for it, to tell you the truth. It wasn’t important to me. Maybe I’m a purist. Maybe I’m more old school than I would like to believe. What was important to me was learning all about the art. Chasing pieces of paper just didn’t interest me. But in my old age, now I think maybe I should have but I don’t know, it still doesn’t interest me that much. I have always believed that you can tell a guy’s level of proficiency when you touch his sword and look him in the eye. At that moment, no piece of paper can hide that fact when you size each other up. In the ancient times, you studied to survive to live to the next day. Anyway, I have since wondered what Sugino Sensei might have thought of my answer. I am sure there were other foreign students who would have jumped at the chance to get a rank. I was again offered the opportunity to test for rank in 2008 by his son but I declined. One of my old students, who studied under me for a decade, did test for rank and he passed all his dan tests easily. Now he is a 3rd dan and working for his 4th dan. I guess that is justification enough and tells me everything I need to know about my abilities. And myself? I have no rank in that art. I guess I am still a beginner.

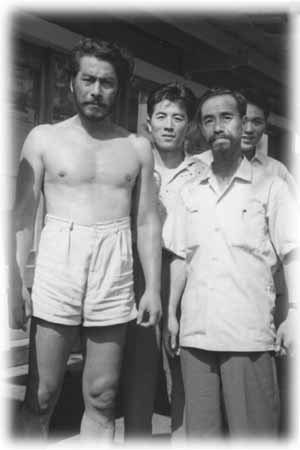

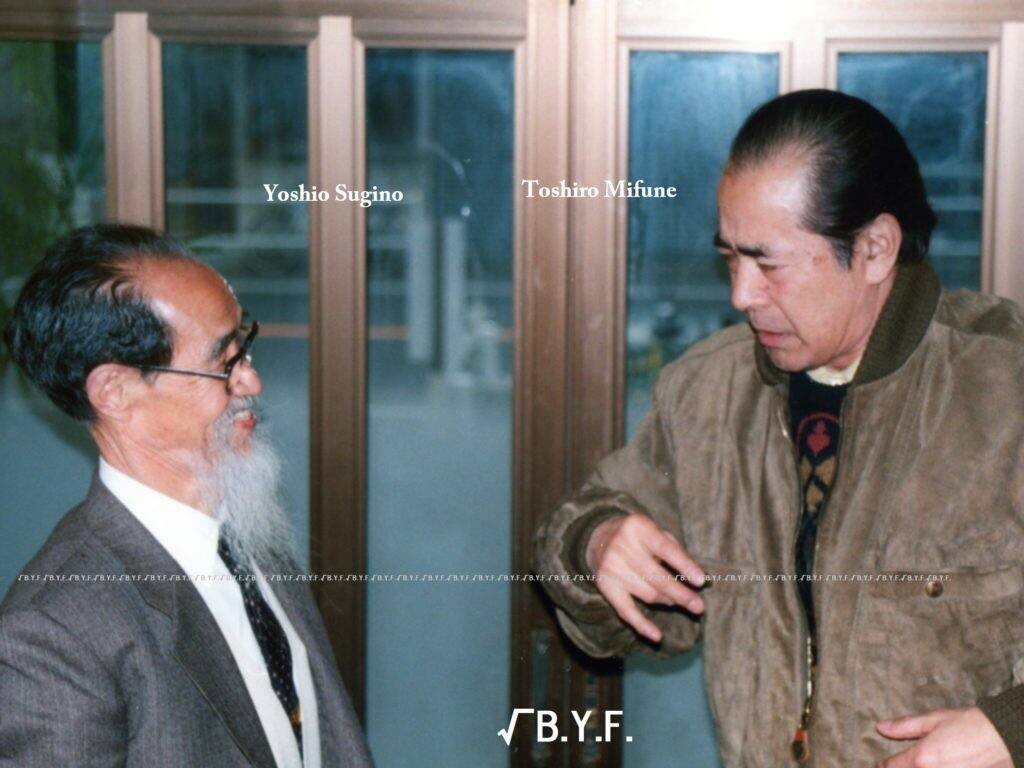

This reminds me of another story. You have heard me mention Sugino Sensei. Well, for those who are not aware of who he is, he was the swordfight choreographer for Director Akira Kurosawa’s two most acclaimed films, Seven Samurai and Yojimbo. I am sure that you have heard of those two movies! Kurosawa wanted the best sword masters to choreograph his movies and Sugino Sensei was recommended to him. (The other sword master recommended was Sasamori Junzo Sensei, the 16th Soke of Ono-ha Itto Ryu but he was tied up with another project at that time so he couldn’t do it. Coincidentally, I studied Ono-ha Itto Ryu under his son, Sasamori Takemi Sensei, the 17th Soke). Anyway, Sugino Sensei was also the swordfight choreographer for Director Hiroshi Inagaki’s epic movie Miyamoto Musashi, which has been retitled as the Samurai Trilogy in North America. That movie won the Academy Award in 1955. That’s a great movie. And as a matter of fact, Mifune Toshiro, the famous actor in all these legendary movies, was Sugino Sensei’s student in Katori Shinto Ryu.

Sugino Sensei and Mifune Toshiro in the old days, during filming

Oh, here’s a story about Mifune Toshiro. One morning, I was sleeping and I got a phone call. It was Pat. He said, “Tong. You have to get to the dojo. Right away!”

I said, “What?” I was half asleep and still rubbing the sleep out of my eyes.

“You have to come to the dojo. There’s a famous person coming in an hour!”

“Who?”

“Mifune Toshiro!”

“Who’s that?” I asked. Because I had no idea who this person was at the time.

“He’s a famous actor.”

“Aww, forget it! I’m going back to bed.”

“You don’t want to miss this one.”

Teacher and student share some good memories many years later

It was my day off. Last thing I wanted to do was go to the dojo in Kawasaki which would take me almost 2 hours to get there and it was raining.

“Nah. I’ll pass. I’ll come the next time he comes.”

Well, did I live to regret that. I missed the chance to meet him as he took time out of his busy schedule to come to Sugino Dojo to pay his respects to his old teacher. Pat and another student got autographs and their pictures taken with this icon of Japanese films. He passed away 4 years later in 1997. I have kicked myself ever since over this missed opportunity. What’s the lesson to be learned here? You only have one chance sometimes in life. Don’t miss it. Like my story, the opportunity may never come again. So don’t be lazy.

Pat McCarthy with Sugino Sensei and Mifune Toshiro, the glorious meeting that I had missed

So there you have a few interesting tidbits of information. Anyway, back to what I was saying before; here is the story which I wrote about Sugino Sensei and the issue of rank:

“One day in the summer of 1992, as Sunday morning class was ending, a group of the European students was getting undressed on the dojo floor. To give a little background, in the summer months in Japan at Sugino Dojo, there would be foreign visitors from other countries who would come to train for a special session like for a month. Usually they were foreign teachers or senior students, black belts all of them, pretty skilled, and probably pretty highly recognized in their own countries for their achievements in martial arts. And some of them yes would come in with airs and the attitude of being a big shot. They would live at the dojo and sleep at the dojo. On one occasion after Sunday class, as we were all preparing to go for lunch and a beer at the local little restaurant nearby with Yoshio Sugino Sensei, they were all taking their hakama off. When Sugino Sensei reappeared after taking his hakama off in an adjacent room, he still had his aikido uniform on (gi top and pants) and it was tied with a white belt. One of the European black belts, a teacher I presume, asked Sugino Sensei: “Sensei, why do you wear a white belt?” He said it in a joking manner, like he was amused. It was translated through an interpreter. I suppose that the man thought that a famous sword master like Sugino Sensei deserved the right to wear a black belt, perhaps as a sign of his rank and status in the dojo. I guess maybe he thought that if anyone had the right to wear a black belt, a symbol of the highest achievement in martial arts, it would be the legendary Sugino Sensei, famed choreographer of Kurosawa’s celebrated samurai classics Yojimbo and Seven Samurai, and teacher to famous actor Mifune Toshiro. Sugino Sensei smiled, nodded his head, pulled on his beard, thought about it and replied kindly with a smile, “Because I am still a beginner.” I watched the reaction as the interpretation came in. There was stunned silence. From thenceforth, the effort and focus and attitude in subsequent practices was of the highest level.

Sugino Sensei, having some fun

Needless to say, I have never forgotten that episode. It really underlines what the true attitude and spirit of Japanese budo should be. Here is an acclaimed budo superstar, a 10th dan in Aikido, a master of Katori Shinto Ryu, a man sought out by Director Akira Kurosawa because Kurosawa wanted the best sword master to choreograph his fight scenes but also a master who understood intuitively what would work best on film, a man who was a direct pupil of both Morihei Ueshiba, the founder of Aikido, and Jigoro Kano, the founder of Judo. And at almost 90 years old, studying for 70 years and teaching for 50 years, still thinking of himself as a beginner. Wow. There are no words to express how it made me feel. They say that great leaders lead by example. Well, I was glad, and I feel eternally blessed, that I was fortunate enough to be there to see this great example of true budo spirit, one of life’s special moments.”

———————————————————————————————————–

Here’s another story. When I interviewed Kajitsuka Sensei in 2008 about what he thought was important for students to remember when studying kenjutsu, he remarked:

“I would like my students to remember that everyone is the same. There is no student. There is no teacher.”

How very interesting! I found this idea very unique and a little difficult to understand, so I asked him what he meant. He said:

“Budo is like climbing a mountain. Everyone is climbing up the same mountain. I am just farther up the mountain than you. I have seen the path that you will take. So, I can point out some of the pitfalls that I have already encountered on my journey up this mountain. However, you must realize that I am still myself going up this mountain. But, I am not a guide telling you where you should go. We are all mountain climbers in the same group. But there are, naturally, some of us with more experience than the rest of the group…”

Wow. .. I was truly astounded when I heard this and I was interviewing him! I have met many teachers before, but I had never heard that before. It was unique. Deep. Insightful. Now you know why I had to follow him. A true philosopher. I knew it was destiny; that I would have a lot to learn from this teacher. Remember, it is all about the relationship between teacher and student. That is the only important thing in budo training.

“Everyone is climbing up the same mountain”

———————————————————————————————————–

So what can we learn from that great interview? One cultural idea is groupness. The Japanese embrace the idea of the group, working for the betterment of the group, and the striving for harmony within the group. For example, Japanese salarymen work like crazy for their company. They work for the group. That contrasts with the Western idea of individuality, where you work for yourself – and in some cases, we can see that there is no harmony in this approach. This is one cultural issue that is very different between our cultures and societies.

Rank can, in the minds of some people, put stress on individual accomplishments which can lead to personal aggrandizement (like ego). How did I do? Where am I on the ladder? How do I get to the next rung? It is what it is and I see the need for it. But in some cases, this goal-driven obsession, if unchecked, can lead to other forms of negative behavior such as an excessive focus on competition, which reveals itself in behaviours like “keeping up with the Joneses”; in other words, keeping up with your peers. Competition deals with victory and defeat, like modern sports, which to the old-school budo people completely contradicts ‘true’ budo spirit, what they call “shinbu”, which is based more on cooperation (harmony or ‘wa’ in Japanese) than competition. This has to do with the purpose of budo.

Truth is buried beneath our egos

Anyway, in my organization, we do not have ranks. We have Study Group Leaders but it is more of an administrative role and position. It’s your turn to teach and pass it on. Administer your group and make sure it grows properly. This mountain climbing idea, which I have adopted from my master Kajitsuka Sensei, focuses on having the more experienced people guiding the less experienced people. Which is basically, in not so many words, the old Japanese Sempai- Kohai system. We all work together.

With rank can come an idea into some people’s heads that they are better than others. This is the idea of competition. I am better than you. I have a higher rank than you. And from the lower ranks of these big organizations, I have heard that some of them feel this way at these big seminars because it is like a caste system. The higher ranks stay over here, the lower ranks stay over there. And never shall the two shall meet. Automatically, there is a sense of division and exclusion. I realize from an administrative standpoint that this is perhaps necessary for efficiency but in some cases, it is detrimental to a sense of group cohesion. So some lower-level students may start thinking: I can’t wait till I get up there so I can start giving the orders, or I want to join that group because it looks so much more interesting. I want to be in that special group. I have seen it here in Canada and I have seen it in Japan too.

Competition breeds ego

Oh yes, let me take an aside just to clear one thing up. I hope that our listeners will not take this the wrong way. I don’t mean to paint all Westerners with one brush. Remember, it’s case-by-case. We have some really great practitioners and some really great people here in the West and we have some who are not so good. I am speaking about character and personality. And I have seen some not so good people in Japan and I have met some really great people there too. So please don’t get the wrong idea about what I say. But in discussing cultural differences and expectations, I find that more education is needed here because we’re not raised with that cultural background about Japanese ideals. These aren’t Canadian ideals and they aren’t a part of the natural fiber of our socialization and upbringing here in North America. So naturally we will find a larger number of people here who have no idea about what real Japanese budo ideally should be like and look like.

———————————————————————————————————–

Here’s another story that will illustrate that. It comes from a friend of mine who is an instructor of kendo from Japan. She was a three-time, consecutive undefeated champion of the tri-county high school kendo championship in her region (which is the northern part of Akita Prefecture). She served as the captain of the kendo team for many years, known in Japanese as “senpō”. And I have to relate this story to you because it is a great story and it really epitomizes this difference in culture and why culture, yes, is important in budo training. I will just read the interview I had with her:

Satomi Matsuhashi, captain and champion (Gunshi Shinjin Kendo Taikai)

Question: Did you look into other kendo dojos near where you live?

Matsuhashi: Yes, I did. Well, I looked into one kendo club near my house first. However, I did not like the impression I got from the instructors.

Question: What happened, if you don’t mind my asking?

Matsuhashi: They were sort of looking down on me with an elegant* attitude. That bothered me. But what bothered me much more is when they quickly changed their attitude towards me as soon as I told them I am from Japan, I was trained in Japan, and have a 3rd dan from Japan. Those three points changed their impression of me significantly. I could not believe this. There were other visitors there at the same time as myself. And one of the instructors treated one other visitor with the attitude like “you are below me”. There was no respect.

Matsuhashi senpō receiving shōjō (certificate) for her team’s 2nd place finish

at the Akita Prefectural Junior High School Kendo Championship.

Question: Can you give us more details of what happened?

Matsuhashi: Well, when I arrived at the dojo, I approached one Caucasian guy first to see if they were still accepting beginners. He said no and pretended like he was too busy to talk to me. After a while, I again asked him if I could watch for a while. He said curtly, “I suppose so, but stay at the back as much as possible.”

I observed him bowing and greeting very nicely to the older senseis as they arrived, who were Japanese and Asians. l decided to approach to one older Japanese man who had a Japanese tare* because I thought he might be a person with a higher position in that club and hopefully could give me some better information.

He was very polite and kind. He advised me to talk to a Korean fellow who was one of the instructors. He was standing with the Caucasian man who I had just talked to. The Korean man was polite and asked me general information, like if I have a bogu* to use, did I have any experience in kendo, and which Dan, if any, I had.

So, through the conversation, they found out that I am originally from Japan, that I was trained in kendo in Japan, and that I passed Shodan-shiken in Japan. At this very moment, this Caucasian man said, “Oh, why didn’t you say so?” I could not believe how much his attitude changed in a second!

Matsuhashi Sensei practices with the students

As we were talking, one university student came up to him (a Caucasian student), and asked if there were any openings in the beginners class. Of course, he was choppy* and gave him very minimal information and tried to get back in conversation with me by saying, “So, did you bring your Bogu? I have to learn some of your techniques from you…”

It made me feel sick to my stomach. I watched him practice kendo with the others. He was trying to show off and show how much better he was than everyone else. I am sure he has a higher dan than me and maybe with a title in this club. But this was not true Japanese budo spirit. It was very sad.

Question: So, in your opinion, what values are important to learn through the study of kendo?

Matsuhashi: Modesty, patience, and quiet wisdom.These might not be noticeable immediately, but I think these are very important. Your true character is reflected in your attitude…

Matsuhashi Sensei (2009)

——————————————————————————————————————-

A great story. So right here, we see what culture in Japanese budo looks like and the cultural differences between East and West in their approach to budo. For some Westerners, it is about techniques because they do not have that cultural backdrop that is present in Japan. But when they leave the dojo, it is back to their Canadian or American life with its ideas of individuality: my rights, my right to free speech, my right to express myself, etc. I come first.

Modesty, patience, and quiet wisdom are vestiges of the Tokugawa reign. That’s Japanese culture. You belong to a group, you think of the group. The group comes first.

Matsuhashi senshu (as senpō) with her team-mates after winning the Gunshi Shinjin Kendo Taikai (District Kendo Championship). The girls with the medals are the 1st team members.

So of course, that Westerner is going to try to steal her techniques. It’s all about him: what he can gain. Does he care about her? No. Does he care about modesty, patience, quiet wisdom? No. He’s aggressive, budo is something to be acquired, taken. He’s very direct. In Japan, things are not done directly. That’s too disrespectful, rude, and arrogant. There’s another cultural difference.

So, if we think about the higher purpose of kendo, or any Japanese sword study, it is not to kill as many opponents as possible so that you can be the best around. You don’t need much training to do that. That’s what this guy was trying to show off: how dominant he was. That’s arrogance.

On the other hand, my master Kajitsuka Sensei said that the higher purpose of sword study (The Way of the Sword; ken no michi, ken dō) was, for old time warriors, the way “to grow a soul”.

Indeed, Yagyu Sekishusai, the second headmaster, wrote a treatise in 1601 called “Heiho Hyakushu” (100 poems on the Art of War). In Poem #91, he said, “the secret principle of heiho is being gentle, kind, courteous, modest, and deferential.” And this is from a guy who had fought on the battlefields in the Warring States Period, killed other soldiers and was almost killed himself. He was wounded by an arrow. His first son fought with him and became a cripple for life. Sekishusai was a war veteran and a tough guy, and isn’t it interesting that what he thought was super important in life and in budo is to be gentle, kind, courteous, modest, and deferential.

Wow.

———————————————————————————————————-

This is the idea of humility in budo. Why do I harp on it so much? Because it is a key feature of the Japanese budo mindset. And the Japanese budo mindset came from Zen. So, for our practice of Japanese budo, what aspects of Zen culture do we need to know? Yagyu Koichi Sensei said that we must let go of our ego. That is Zen. Your ego clouds your mind.

That is the basis of the idea of ‘Katsujinken’: the living sword or Life-Giving Sword. In a fight, we must be able to see clearly. That requires an open mind. Free from ego and preconceptions. Actually, this also applies to your dan testing. In high pressure situations, if you get fixated or obsessed, you will lose, or screw up. But back to what I was saying: With an open mind, you can be creative and not constrained. You can be free. Free to adapt. To flow with the moment.

Facing an opponent (and life) with an open and free mind

That is scary. People become afraid. With freedom, there is no structure. My ego depends on having that structure there to bolster my sense of self-worth. That’s why trying something new, going in a new direction, throwing everything away, is so difficult for people.

You need to be willing to step out that door. The Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu said “The thousand mile journey begins with one step.” He is so right. The first step. The leap of faith.