Here is the full text of the lecture portion of this special episode. You can hear this podcast on the Media page.

__________________________________________________

Tokushikai Canada’s “Special Episode – with Douglas Tong”

Interview with Douglas Tong

Full text

copyright © 2021 Douglas Tong, all rights reserved.

———————————————————————————————————–

Special Episode – An In-Depth Look at the Roles of a Teacher with Douglas Tong

Introduction

Douglas Tong is from Orangeville, Canada, and has been teaching kenjutsu since returning from Japan in 1994 at Tokumeikan. He now continues his studies under Mutoh Sensei’s successor, Master Yasushi Kajitsuka, the 11th soke of Yagyu Shingan Ryu Taijutsu (Edo-Line) and 3rd shihan of the Ohtsubo Branch of Yagyu Shinkage Ryu.

In his professional life, Mr. Tong has a Master’s Degree in Education. He taught overseas for many years in Japan. When he returned to Canada, he was employed as a lecturer and course instructor in the Department of Applied Linguistics at Brock University. He is currently a public schoolteacher with the Peel District School Board, the second largest school board in Canada. All in all, he has 30+ years teaching experience (20 years in public school teaching, 5 years at Brock University, and 5 years overseas).

An experienced Master Teacher, Mr. Tong has served for years as an Associate Teacher (mentor) for many Teacher-Candidates (interns), mentoring and instructing young teachers who are just entering the profession. Mr. Tong is also dedicated to making a difference in the schools that he works in, serving in various administrative committees to do with staffing, culture and climate, and leadership. He is furthermore dedicated to improving the lives of the teachers he works with. Serving as Union Steward at his school, he safeguards the rights of, mediates for, and counsels teachers. Finally, Mr. Tong is a member of the Ontario College of Teachers in good standing.

Mr. Tong is the leader of the official study group (keiko-kai) for the Ohtsubo Branch in Canada under Master Kajitsuka.

In his words:

“Kenjutsu (Japanese sword-fighting) is endlessly fascinating. Whether you are fighting with two swords, have only a short sword, fighting against a naginata or a spear, dueling sword versus sword, or even trying to survive when you have only your bare hands against an opponent wielding a sword (“muto” – the famous theory of No-Sword), there is always something to learn: about the weapon, the tactics, the psychological mindset, the style’s particular approach, or even about yourself. These moments of realization, these sudden epiphanies. That is the real beauty of the art.”

———————————————————————————————————–

Budo and Teaching

In Budo, there are two aspects of training that all practitioners will eventually confront in their budo journey: one is learning and the other is teaching.

First, when one starts budo, one is in a learning mode, trying to acquire as much information as possible, trying to develop as much skill as possible. We are in a student mindset and our job is to learn and absorb. Then, inevitably, as one gets older and more experienced in the art, one will have to teach it to others, to the new students who will walk in the door.

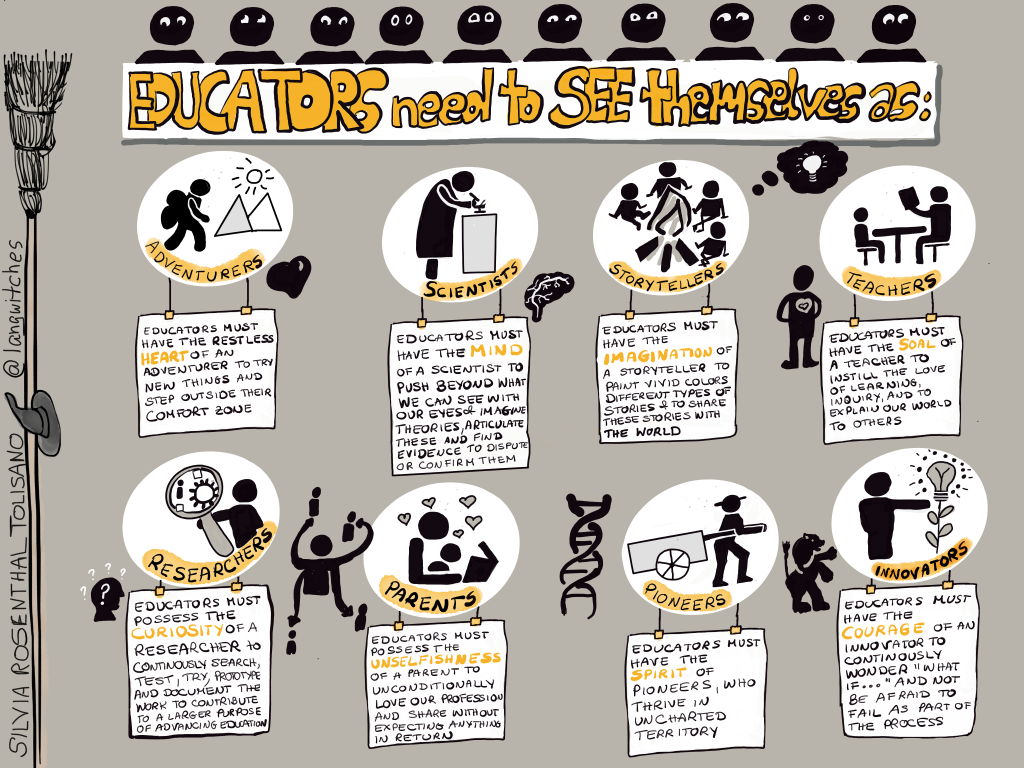

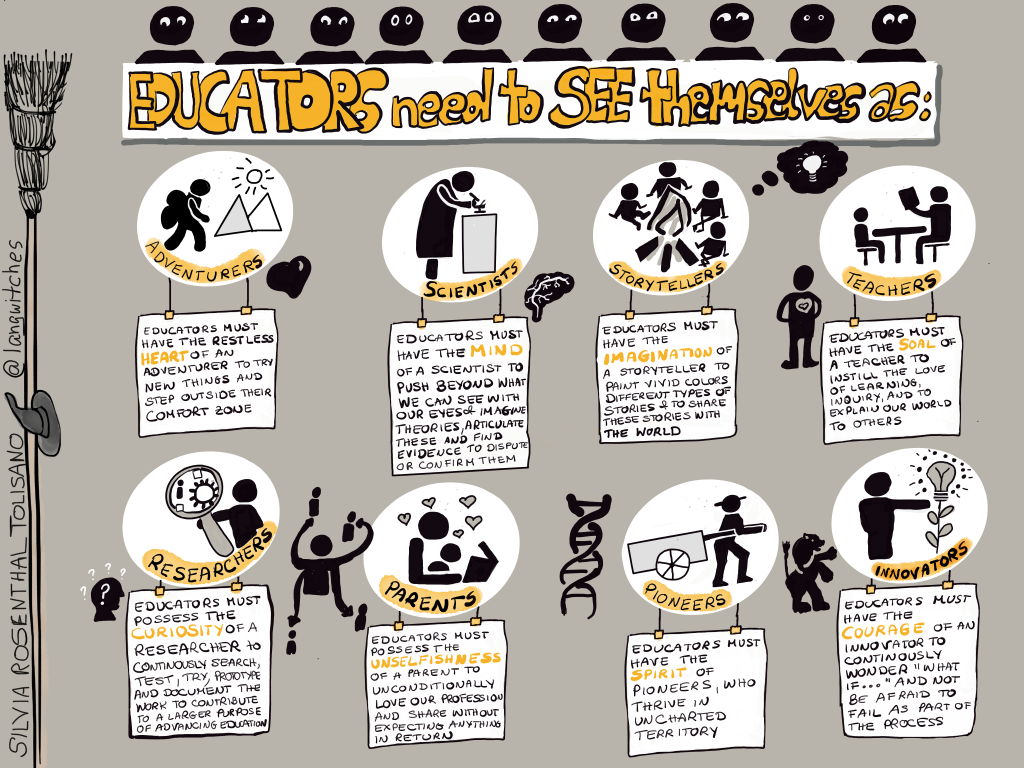

On the topic of teaching, there are a myriad number of issues on how to teach. But one visual chart caught our eye and our interest and that was the question of “How should Educators see themselves?”

And in this chart, the authors break it down into 8 viewpoints. Teachers should see themselves as:

1) Adventurers

2) Scientists

3) Storytellers

4) Teachers

5) Researchers

6) Parents

7) Pioneers

8) Innovators

This very question goes to the heart of “why do we teach?” What drives us to teach and what should we aspire to do in this job of teaching?

Teaching can become very hum-drum and a tedious routine. We have probably all saw teachers who show up to class and just blandly cover the material. “Ok, this is what we are doing today.” There is no passion, no engagement, no wonder. It is obvious that they view teaching as a job and go through the motions. Teaching to them is a chore. Really, they don’t especially enjoy teaching.

Other teachers are there for the power and the glory. Especially in budo, teaching is a sign and symbol of high rank and achievement in the art. In some cases, you are expected to teach once you reach a certain high rank. For some people, this is when the ego begins to get big like a balloon. They are now the center of the universe, or at least their dojo. These are symbols of their status in their art. They may not like teaching but they like the status and power that comes with the position of teacher or master.

Being a good martial artist, being good at martial arts, doesn’t mean that you are good at teaching it. Because teaching it is not about you doing it but instead, about getting the student to learn it and do it. So it’s not about you anymore, it’s about them.

Teaching is about getting the students to do it

So what separates the mediocre, hum-drum teacher from the really excellent teachers?

In thinking about this subject, I went back over my interviews with my master and this one part kept coming back into my mind. So I will just read it to you, if you will bear with me for a minute.

Question: As a teacher, what do you try to teach your students, apart from just technique?

Sensei: I try to teach my students three rules to live their life by:

1. Love what you do. This is the most important.

2. Do it from the heart. We say “kokoro”. In other words, do it with all your heart and soul.

3. Continue it. Keep doing it. Don’t stop.

These are the three main rules. Now after these three, I also recommend to my students two more:

4. Don’t be afraid.

5. Take things on. By this, I mean, try new things.

So these are the 5 things he mentioned as really important. And as we shall see in our discussion, these 5 points keep coming up over and over again. So let’s take a look at this chart and work our way through it, section by section, to try to see how it can inform us about our basic question: what makes a good teacher in budo?

Kajitsuka Sensei and Mr. Tong in Yokohama (2008)

————————–

The first section is the Adventurer:

“Educators must have the restless heart of an adventurer to try new things and step outside their comfort zone.”

An adventurer. That’s an interesting idea.

In our style, Yagyu Shinkage Ryu, our 2nd headmaster Yagyu Sekishusai had a famous saying. He said that you should surpass the self that you were yesterday.

What does he mean by that? Well, Yagyu Nobuharu Sensei, the 21st Soke, gave an explanation in his speech in 1993 in New York City during his demonstration of the art at the United Nations. He said:

“A continuous improvement of the self is the way of the Yagyu Shinkage Ryu. In many cases, we get satisfied when we reach a certain level. You must not be satisfied to reach one level of skill or only one target. For example, if you climb a mountain, once you reach the top, you see another, larger mountain. You must now go to that taller mountain. If you feel happy with your present standing, then actually you are already losing your skill level. Instead, you must keep trying to improve and eventually you will find something to push yourself forward from within. Continuously trying to improve at the sword is related to the same effort made in Zen training. Training in the sword, in Yagyu Shinkage Ryu, means a constant improvement of the self through training in how to use the sword.”

So, this is the spirit of striving and reaching for greater heights. This is the spirit of exploration. In fact, if you recall my interview with Kajitsuka Sensei, he said his rule #5 was to “try new things”.

Now the definition above also mentioned that the heart of an adventurer also means to step outside our comfort zone. That is important too. I interviewed Kajitsuka Sensei in 2011. For those who are not aware, Kajitsuka Sensei is the Secretary-General of the Nihon Kobudo Shinkokai, the Society for the Promotion of Japanese Classical Martial Arts and Ways, which is the oldest national association of the classical styles of Japanese budo and bujutsu (what they call “koryu”) in Japan. I interviewed him about the dangers inherent in associations. One particular quote was very poignant. He said:

“In the case of kobudo, each ryuha has been protecting its own unique tradition and interests for several hundred years. Therefore, it is not unreasonable that they are very self-respecting. In other words, they are proud of what they do and who they are. It is natural to feel this way. However, the danger is that it is easy to become exclusive. By this, I mean that there is the possibility that they do not recognize other ryuha. There is also the danger that they will slander each other. If this happens, the association will not be unified.”

Kajitsuka Sensei (3rd from the left) is a member of the Board of Directors of the Nihon Kobudo Shinkokai.

That is the comfort zone and it is natural for some people and organizations to not want to leave that comfort zone, their own little bubble. Like the proverbial ostrich that just wants to stick its head in the ground and not acknowledge that there is a larger world out there. So what is the solution for an association to succeed and to grow? He remarked:

“First of all, it is important to deepen the exchange between schools. Each ryuha is founded under the influence of other ryuha. What I mean is that each ryuha does not come into being in a vacuum. They are influenced by, and also in their turn influence other ryuha. They are all inter-connected with each other in many ways. You can understand your ryuha in a deep way by studying not only your own ryuha, but also other ryuha as well. But this is only possible through the interchange and exchange between the various ryuha.

In addition, through the interchange between the ryuha, I hope that all kobudo practitioners will come to see that all martial arts have a common root and in the end, they all have the same purpose. If we can achieve this kind of understanding, we can become more united and ultimately, we will be able to achieve greater things.”

Kajitsuka Sensei at the Opening Ceremony of the 43rd All Japan Kobudo Demonstration in Tokyo.

This is getting outside your comfort zone, leaving your tiny little bubble and experiencing the world. As a teacher, you can’t just stick your head in the ground. You can’t just do the easy, comfortable things over and over again. That gets very boring. And over time, as a teacher, you will get too comfortable to the point that you cannot change. I have seen it happen in regular teaching. Teachers get so set in their routine that they refuse to change. They are teaching from the same book in the same way 20 years later. They are stuck, and have limited themselves. Pretty soon, they know nothing else. They haven’t kept up with the trends and soon they are out of touch with what is happening in the outside world. That is when they become afraid to change. There’s too much ground to cover; they would have to become a beginner again. And that they cannot stoop down that low, to start again.

So how do we avoid this kind of situation? It starts by not being afraid to try new things, and being adventurous. When you embrace change, you will not fall behind. So, as a teacher, trying new things is actually a good idea. This is the heart of the teacher as adventurer: the love of trying new things and experiences.

When my luggage did not arrive at San Diego Airport, I had to teach my first international seminar in street clothes. With no clothes, my first seminar in Tijuana, Mexico was an adventure I will never forget!

————————————————————————————————————–

The second section is the Scientist:

“Educators must have the mind of a scientist to push beyond what we can see with our eyes and imagine theories, articulate these and find evidence to dispute or confirm them.”

In this way, you have to be dedicated. This is Kajitsuka Sensei’s “Rule #2: Do it with all your heart.” Dedicated to finding out the “truth” of your art, knowing all about it.

In this way, teachers should aspire to be a subject matter expert. That means being knowledgeable in that art, knowing all about that art. It is also about being skilled; it’s about ability. You can be very knowledgeable, like an encyclopedia. But you also have to be able to do it well.

Being an expert means being knowledgeable in the art

Now, the key to becoming a subject matter expert requires either having or if not, then developing, some essential character traits in you:

Things like being analytical: being able to analyze your art.

Another one is being open-minded: in order to see the possibilities and even conflicting information. This also entails sometimes being dispassionate in your analysis of your art and not just adhering to established dogma.

Expertise requires experience and study. Therefore, you should be disciplined and dedicated to practicing your art. This is Kajitsuka Sensei’s Rule #3: “Keep doing it.” Part of the mind of a scientist is their methodology. They keep pushing the limits, testing, and finding out the limits. That requires repetitions. In budo, that requires repetitions of practice; the same is true in sports and athletics. They need to train endlessly, to hone and perfect their craft. Same as we do in budo.

So what does this have to do with teaching? Good teachers are usually in most cases, great learners as well. They know “how to learn”. They have learned how to dissect and break down kata into discrete movements, and then break down these movements into specific skills, into the fundamentals. Once that is done, they can make it comprehensible for their own students to learn them.

Good teachers dissect and break down kata for their students into discrete, comprehensible movements

Having the mind of a scientist also entails following a scientific method and having a methodology for learning. Deciding on and setting out a blueprint for learning that helps the student to master the material. That is also the job of a teacher: to provide that roadmap to mastery. That takes some planning and thought, and some imagination. But you must enjoy constructing learning opportunities for your students. This is the mind of the teacher as scientist: the love of designing learning.

————————————————————————————————————–

The third section is the Storyteller:

“Educators must have the imagination of a storyteller to paint vivid colours, different types of stories, and to share these stories with the world.”

I teach Grade 1. Part of my job is not just to teach 1 + 1. Simple math, science, and language arts like how to form a sentence are important, yes. Just like a teacher of iaido for instance. Your job is to teach them how to cut. But is it only that? The world would be a pretty dry place if that was all we taught.

I believe that it is also important, as a teacher who has the responsibility to socialize the next generation, to share the richness of our values, our norms, and our ways of thinking and acting that make us who we are as a culture. To do this, a teacher needs to be a role model, and also a good storyteller, to tell the stories of our culture. In this way, teachers need to share the joy, leave a life-changing impact, inspire, and model.

In budo styles with rich histories, these stories are part of the culture, mythos of that specific art and that specific style. Styles are cultures: they have their own way of thinking and acting. Mannerisms like Soke said.

The Yagyu Museum, containing all the treasures and history of the Yagyu family, on the grounds of Yagyu Village

The Japanese Government has named or designated some styles as National Treasures, because they are, in their definition, “intangible cultural artifacts”. Notice the words they use: cultural artifacts. They are exemplars of a culture. In this case, a budo culture.

It then begs the question: What is culture?

Culture is defined as ‘the cumulative deposit of knowledge, experience, beliefs, values, attitudes, religion, and ways of seeing the world and acting in it.’

As an aside, I want to mention a part of the interview I conducted with Kajitsuka Sensei in 2015. I asked him about the purpose of this Association. He answered:

“… as regards our kobudo association, I believe we have an important purpose. Kobudo is not purely about fighting and combat only. Yes, the arts that our members practice are combat arts and so naturally there is a focus on combat, on fighting. But Kobudo also includes the wisdom of how to live; how to live as a person, as a human being. If we think in terms of a single style, this is ultimately what the founder of that specific style learned under the risk of his life on a battlefield. Therefore I think that Kobudo is a precious property of not only Japan but also of all human beings, no matter what nationality they are.”

“How to Live”: this is ultimately what the founder of a style learned under great risk to his life on the battlefield.

So, a style basically is the sum product of the experiences of a Founder; the lessons he learned on the battlefield. Of course, he learned which techniques are most effective at killing opponents. But this Founder also learned “the wisdom of how to live”, how to stay alive and keep staying alive.

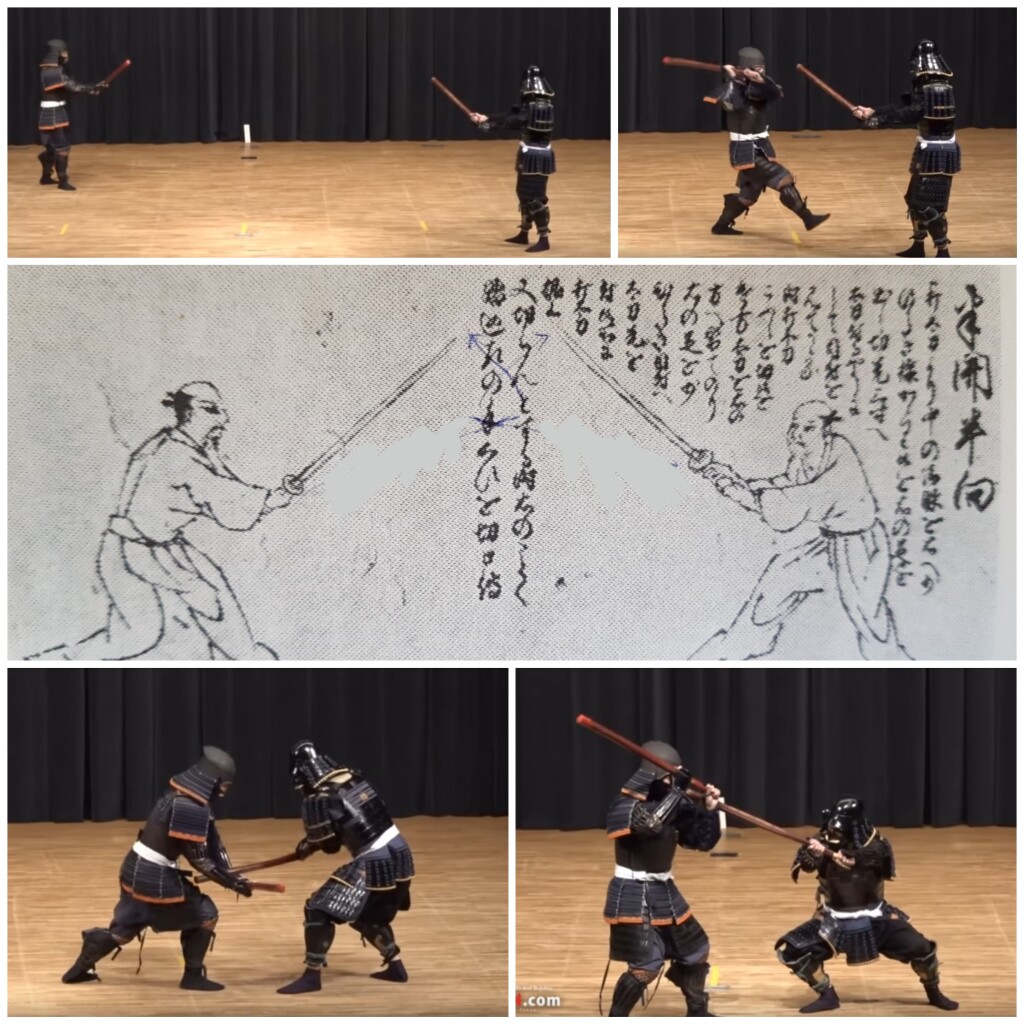

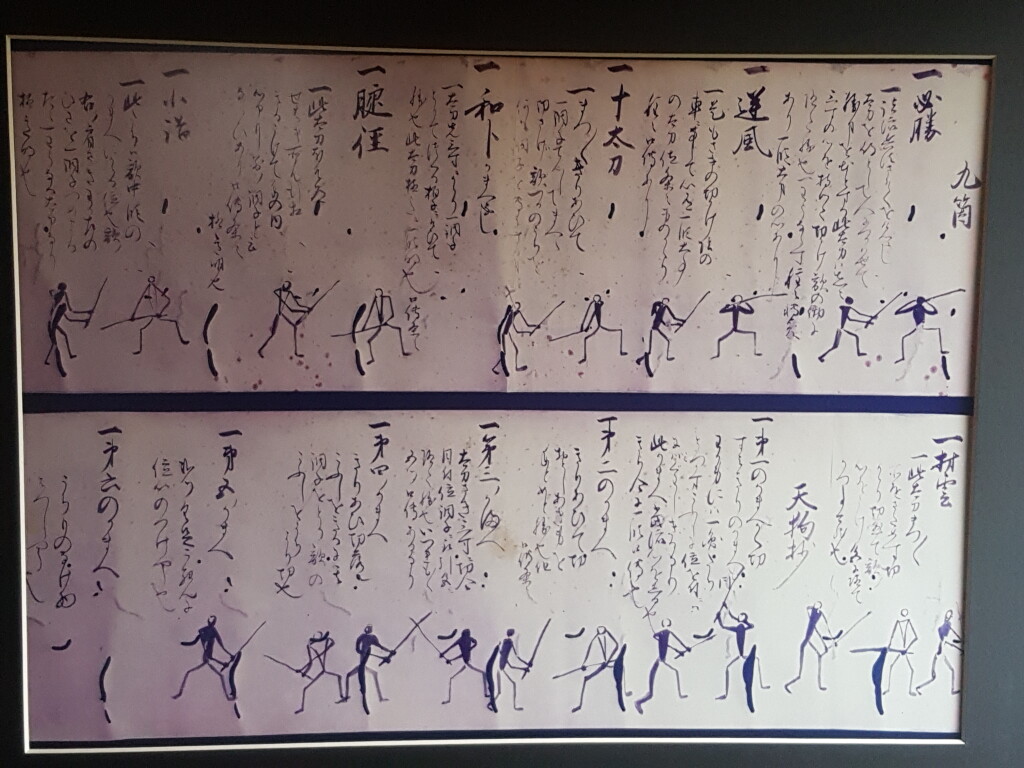

So let’s think about that for a while and use a style to illustrate what that might mean. Recall that the definition of culture is ‘the cumulative deposit of knowledge, experience, beliefs, values, attitudes, religion, and ways of seeing the world and acting in it.’ So, a style is that deposit of knowledge by the Founder, what he learned at the risk of his life. He survived that harrowing experience and lived to tell the tale to others, to advise and warn his descendants and followers. And he continued to live and that wisdom and knowledge kept him alive throughout his lifetime: these are the ‘beliefs, values, and attitudes’. For example, in Muso Shinden Eishin Ryu iaido, there is a kata at higher levels where you cut three opponents who are hiding in the bushes along a pathway. That is an experience the Founder actually experienced and had to deal with. That is a valuable life lesson on what to expect along pathways, and more importantly, how to deal with this scenario. It is both advice and warning. It is a ‘way of seeing the world and acting in it’. In our art of Yagyu Shinkage Ryu, there is a kata that deals specifically with fighting two opponents. How do you fight two opponents who are rushing at you at the same time? This is the wisdom of how to stay alive.

A scroll containing the fighting techniques of the style: “a deposit of wisdom from the Founder”. Priceless.

So a style is a culture, and you can also view the curriculum of techniques and katas as basically a set of stories from that culture, a culture born in blood but perhaps not ending in it. These stories shed insight and in some styles, some cultures, can illuminate your life.

I will give an example from Yagyu Shinkage Ryu, which is very famous in Japan for its core philosophy of the Life-Giving Sword, the Sword of Peace. And one of the famous stories involved Kamiizumi Ise-no-Kami Nobutsuna, the Founder. In this episode during his journey to Kyoto with his two disciples, they came to a village near Myoko Temple, where they found that a bandit had kidnapped a child and was trapped in a hut, threatening to kill the child with his sword if anyone came in. Well, suffice it to say that Nobutsuna went in unarmed at great risk to his life and rescued the child. It is so famous that Director Akira Kurosawa used it as the opening scene in his classic movie Seven Samurai. He used it to illustrate the bravery of his man character Kambei, which he modelled on Kamiizumi. Anyway, this episode is a perfect example of Muto-dori (the concept of ‘No-Sword’), one of the highest principles of Yagyu Shinkage Ryu, being able to fight someone with anything, even empty-handed if necessary, and not being afraid to do so, being mentally and spiritually ‘ready’ to do that. That is the culture of Yagyu Shinkage Ryu. That is its belief system: being free of fear, being brave in the face of danger. That is what the Founder learned at great risk to his life and the tremendous life lesson that is teaching us. It is a way of seeing life, approaching life and how to live it well and fully.

The opening scene of Seven Samurai re-enacts the true account of Kamiizumi’s heroic deed at Myoko Temple

Being a storyteller? I just gave you a perfect example of that. Being a good teacher is also being a good storyteller. Because it is our responsibility to pass these stories on to the next generation. These stories enrich the art. Some practitioners approach an art just looking at its techniques. They are only interested in its techniques. But that is kind of empty. Just cut, cut, and cut? I think of this as the bones. Here’s a story from my days in Japan. I attended a special 3 day symposium on budo culture at the Budo University in Chiba in 1991.

Attending the 3rd International Seminar on Budo Culture at the Budo University in Chiba

Anyway, you meet a lot of high-level practitioners of many martial arts there and one guy I remember was a 5th or 6th dan iaido from Iran. Super nice guy but he couldn’t speak any English at all. The only English word he knew was “cut”. And he was trying to teach us about some high-level iaido katas. And I vividly remember him saying over and over: “you cut, and you cut, and you cut!” It was kind of funny but I guess essentially correct! You cut, and you cut, and you cut. I suppose you could approach iaido that way, from that kind of utilitarian approach. But it is empty. I believe that he wanted to tell us more but it struck me at that moment, that yes, styles can be viewed in that way, as just a collection of techniques, a collection of bones.

Having discussions on sword-fighting with the kendo masters at the seminar was one of the highlights of this adventure

But you need some meat on those bones, to give it life. Storytelling adds that meat to enliven those empty, soulless bones. This adds the vivid colour, the vibrancy to the techniques, that makes them come alive.

Storytelling encourages us to dream, to imagine. What is the meaning of the technique? Why did the Founder choose this one and not that one? What is he trying to tell us? So the job of a teacher is also to provide the stories that allow the students to imagine and to feel, or to ‘taste’, the wonder of the art.

My first sword teacher Sugino Sensei said that it is important to “feel the fascination (myōmi) and to understand the mystic depth (myōri) which is deeply hidden in the technique”. Myōmi can also be translated as ‘fine taste’ and myōri as ‘exquisite logic’, even ‘mystery’. So Sugino Sensei is saying that in the techniques are hidden these mysteries and messages that the Founder is trying to tell us. It is our job as a teacher to unpackage them and help the students to get a taste of them.

Meeting Yagyu Nobuharu Sensei (the 21st Soke of Yagyu Shinkage-ryu) at the Budo University: truly a memorable moment

So this is the imagination of the teacher as storyteller: the love of telling stories.

————————————————————————————————————–

The fourth section is the Teacher:

“Educators must have the soul of a teacher to instill the love of learning, inquiry, and to explain our world to others.”

This brings to my mind a story.

Years ago, I was walking through the halls of the high school where my youngest son takes Japanese lessons on the weekends and I noticed this award plaque on the wall. It had the engraved photo of the person it memorialized and the following words describing the award.

————————————————————————————–

The Margaret Thompson Memorial Award

Margaret will always be remembered as a caring and dedicated teacher who had the ability to bring out the best in her students. Her genuine concern and empathy for students facing a myriad of problems was evident in her daily contacts with them and resulted in helping many to develop their self-esteem. She gave of herself to everyone.

Students who too often arrived feeling unworthy and unloved left knowing that they had a caring friend and ally in Margaret. She helped her students through many difficult times, juggling crises and easing the way with a gentle humour and a sense of calm. Margaret will always be remembered with much love.

This award will be given to a graduating student who displays an open, caring personality, a sense of humour, leadership qualities, and a love of life.

The Margaret Thompson Memorial Award plaque

————————————————————————————–

While people were rushing to and fro through the halls in a frenzy to pick up their children, I was standing there quite deep in thought, looking at this plaque and thinking about what it meant.

“Margaret will always be remembered as a caring and dedicated teacher…”

She cared for her students. She was dedicated to her job. Maybe teaching is not just a job, like any other office job. 9 to 5, punch out and go home, free to forget about it. No, teachers think about their students 24-7. Reflecting, analyzing, mulling it over and over. It is a calling, like religion. Driven by ideals. You have to be dedicated to keep at it year after year, caring for generation after generation of students who come through your door.

Caring for generation after generation of students: that is the calling of the teacher

“Her genuine concern and empathy for students…”

Another set of traits generally considered essential to have as a teacher. If you don’t care about your students, get out of teaching. If you cannot sympathize with your students’ various plights, find a new profession. You will not be a good teacher unless you are genuinely concerned. A lot of people can fake it or go through the motions of pretending that they care but really don’t, but if you are doing this, you are just lying to yourself.

My friend, Matsumoto Sensei, helping the kids with their kendo gear

“… resulted in helping many to develop their self-esteem.”

This is really the crux of the matter. In many cases, it is all about self-esteem. In sword arts and other martial arts, it is about self-confidence. Confidence in one’s ability and feeling good about what they are doing and how well they are doing it. The teacher’s job is not to belittle the student or to be one step ahead of the student or keep them down (ie. keep them humble and submissive) or other such nonsense. If you are thinking this way, you have your own issues that need to be tended to first.

Teachers help students to develop themselves

“She gave of herself to everyone.”

There is that piece about selflessness (i.e., self-sacrifice) again. Teaching is a tough job because you have to give of yourself.

“Students who too often arrived feeling unworthy and unloved left knowing that they had a caring friend and ally in Margaret.”

Well, this is true in many cases. Students come looking for answers. If they had the answers, they wouldn’t come. And the answers that the students are seeking in martial arts are usually not of the “How can I beat this guy to a bloody pulp?” variety. They might be looking for ways to better themselves, be more at ease, more confident, feel better physically, feel better mentally, feel better spiritually, look better, meet new people, be part of a new group, etc… Basically enriching their lives in some fashion. So in some ways, a teacher is also a psychiatrist and self-esteem coach.

Teachers help students to enrich their lives

“She helped her students through many difficult times, juggling crises and easing the way with a gentle humour and a sense of calm.”

The key words here are gentle humour and calm.

Humour is essential. Too serious is no good. Too loose however is also not good. Some dojos are so serious and uptight you can hear a pin drop on the floor and the students live in mortal fear of doing something wrong. Other dojos are so loose it seems like it is some kind of party-time or a daycare gone wild. Ease the tension with a calm and purposeful atmosphere.

“… She helped her students through many difficult times, juggling crises…”

A teacher wears many hats: educator, social worker, confidant, manager, psychologist, organizer, psychiatrist, counsellor, nurse, therapist, spiritual advisor, etc…

It’s all about good classroom management and good people management. You are the calm in the storm.

The teachers at the Nikka Gakuen Kids Kendo Club in Toronto

“Margaret will always be remembered with much love.”

Well, there it is. The ultimate statement of praise for a good teacher and a job well done.

So this reminds me of Sensei’s Rule #2: “Do it with all your heart.”

It is difficult to teach if your heart is not in it. Love, enthusiasm, passion. These all come from the heart.

There is also Rule #1: “Love what you do”.

Love of the art, love of learning, love of teaching, love of practicing and training, and love of students.

Yes, teachers must cover subject matter material. That’s the easy part and maybe 10% of our day.

Inspire and guide. Now that is more difficult.

On one of my textbooks on what makes a good teacher, there is this photo that I remember to this day. It was a photo of a teacher with a sweatshirt on which was emblazoned the words, “I don’t teach. I inspire!” How very true. If we do not inspire them to do it, the students will not do it themselves. It is our job to light that fire.

And it all comes from the heart. This is the soul of the teacher as teacher: the love for the students.

The parents, students, and teachers of the Nikka Gakuen Kids Kendo Club: all done from the heart

————————————————————————————————————–

The fifth section is the Researcher:

“Educators must have the curiosity of a researcher to continuously search, test, try, prototype, and document the work to contribute to a larger purpose of advancing education.”

This brings to mind an episode I had with my thesis advisor who was a well-respected professor in her field. She was widely published and very knowledgeable. One day, I was in her office and we were talking about how does one know. Surprisingly, she admitted to me that she is not smarter than anyone else. I objected and said, “You have a Ph.D. That means that you know a lot. That you’re an expert.” To which she replied to me, “Having a Ph.D. doesn’t mean that I am smarter than others. It just means that I ask better questions. I am really good at asking the right questions!” Frankly, I was astounded by this revelation. One, that she was not so smart by her own admission. But more importantly, that being an expert doesn’t mean that you possess some magical ability to store knowledge or have some kind of astounding IQ, but instead, that you get better and better at asking the right questions.

Asking questions: the key to progress

Long story short, she told me that the key is to keep researching. The road to knowledge is not magic but hard work, continuing to search for answers. It completely changed my perception of professors. They are the seekers, asking better questions to advance knowledge. When you ask a good question, you will get a good answer. Which will bring up more questions, which then lead to more and perhaps different types of questions. That is the quest or knowledge, pushing the boundaries of accepted knowledge or some might call it dogma. In this way, they are lifelong learners, never satisfied with their current state of knowledge but forever questioning. That, she said, was how we expand our knowledge. That is progress.

Continually doing research and searching for answers is the way of the Researcher

I have heard iaido practitioners and teachers complaining about “The new fashions from Paris,” whenever new changes come from Japan. But in a way, this is the same process of questioning and experimenting that is necessary to keep updating and advancing the knowledge base. Otherwise, it becomes a stale, dead art if it remains unchanged. Basically, it will become a museum piece, immutable, forever under glass.

When I interviewed Kajitsuka Sensei in 2008, I asked him about teachers and students. He said there is no teacher and there is no student. I was totally perplexed. I said, what do you mean there are no teachers and no students? He said:

“Here is an analogy. Budo is like climbing a mountain. Everyone is climbing up the same mountain. I am just farther up the mountain than you. I have seen the path that you will take. So, I can point out some of the pitfalls that I have already encountered on my journey up this mountain. However, you must realize that I am still myself going up this mountain. But, I am not a guide telling you where you should go. We are all mountain climbers in the same group. But there are, naturally, some of us with more experience than the rest of the group…”

Wow. We are all mountain climbers climbing up the budo mountain. He is talking about researching budo principles. He himself is still climbing that mountain, still researching, still exploring. He hasn’t found his answers yet. That was inspirational to me.

Kajitsuka Sensei interviewing the descendant of our Founder Kamiizumi Nobutsuna: he is still searching for his own answers

So from these two inspirational teachers of mine, I have learned that research is also an integral part of our job as teachers. This is the curiosity of the researcher: the love of researching and advancing our knowledge base.

————————————————————————————————————–

The sixth section is the Parent:

“Educators must have the unselfishness of a parent to unconditionally love our profession and share without expecting anything in return.”

This idea of unselfishness is very telling. We always ask new teachers: why do you teach? That is a good question. If they say they do it for money, then they will not last long. There is no money in teaching budo.

I think it boils down to: you love the art. And when you love the art, you want to share it with others, to share the joy with others, to have others join you in enjoying this art. It’s about love.

When you love your art, you want to share it with others

Budo is in some ways a lonely road. It is built into the basis of the art, in a way. This is because as an art, it is a means of survival, fighting against an enemy. It’s a very personal thing, when you fight one-on-one with an enemy, face-to-face. Everyone and anyone can be an enemy. In this way, it is lonely. It is not cooperative. Your trials and tribulations in your journey in budo are very personal.

Yes, budo is a journey of discovery and we need companions on this road to discovery, discovery about the art and also discovery of yourself. When I came back to Canada, I had nobody. I knew nobody. I couldn’t train indefinitely by myself. I needed training partners. So you need to create and develop and grow your own training partners. This is how it usually begins. This is how I built this group from nothing. We came from very humble beginnings.

Teachers need students as much as students need teachers: You need to create your own training partners

Do I expect anything in return? No. It was done for my own selfish purpose: to have someone to train with. And yet, I will not live forever. My responsibility to the art that I have learned and what my teachers have taught me must not die. I guess that is my debt to my teachers, a debt of honour. They trusted me, had faith in me, believed in me. For me not to honour that, to let it die, would be selfish. In this same way, I entrust it to the future. There are some great lessons in what I have learned. Things that people will spend hundreds of dollars in trying to read about in a self-help book or a video. And to top it off, I teach for free even! Imagine that.

My first master Yoshio Sugino Sensei said:

“Traditionally, the teaching of budo was from teacher to student, heart to heart, without words.”

Teacher to student: a communication that is from heart to heart, without words

That also is a form of love. The teacher loves his or her student, much like a parent loves a child. We can never repay our teachers, especially if they pass away. But we can pay it forward by teaching our own students and passing on the legacy.

Paying it forward: passing on the legacy

In 2015, one of my students from Mexico, named Hector, interviewed Kajitsuka Sensei about Yagyu Shingan Ryu, a comprehensive battlefield style that includes study in many weapons but is famous for its impressive jujutsu techniques. By the way, Kajitsuka Sensei is the 11th Lineal Headmaster (the Soke) of this style which was founded at the beginning of the Edo Period. Hector wrote about it afterwards. It is such a great story that I will recite it for you now. It went like this:

“I asked Kajitsuka Sensei, “What are the most important things that Yagyu Shingan Ryu practitioners should take into account?” He replied:

1. Love humans.

2. Train nonstop to develop physical strength and inner strength.

3. Always be gentle, never engage in violence.

4. Never fight with anyone but yourself.

5. Have a GREAT hope in humanity.

Upon receiving this response and after hearing his explanations on each of these points, I realized that this seminar, these techniques, and martial arts in general are empty unless the practitioner truly wants to become a better human being.

He went on to explain that schools have changed, the purpose has changed from killing to preserving life, especially in Yagyu Shinkage Ryu. We must train nonstop. Through the practice of Kata, only then can we hope to wrap ourselves in and come to understand the spirit, mind, and hopes of the founder.

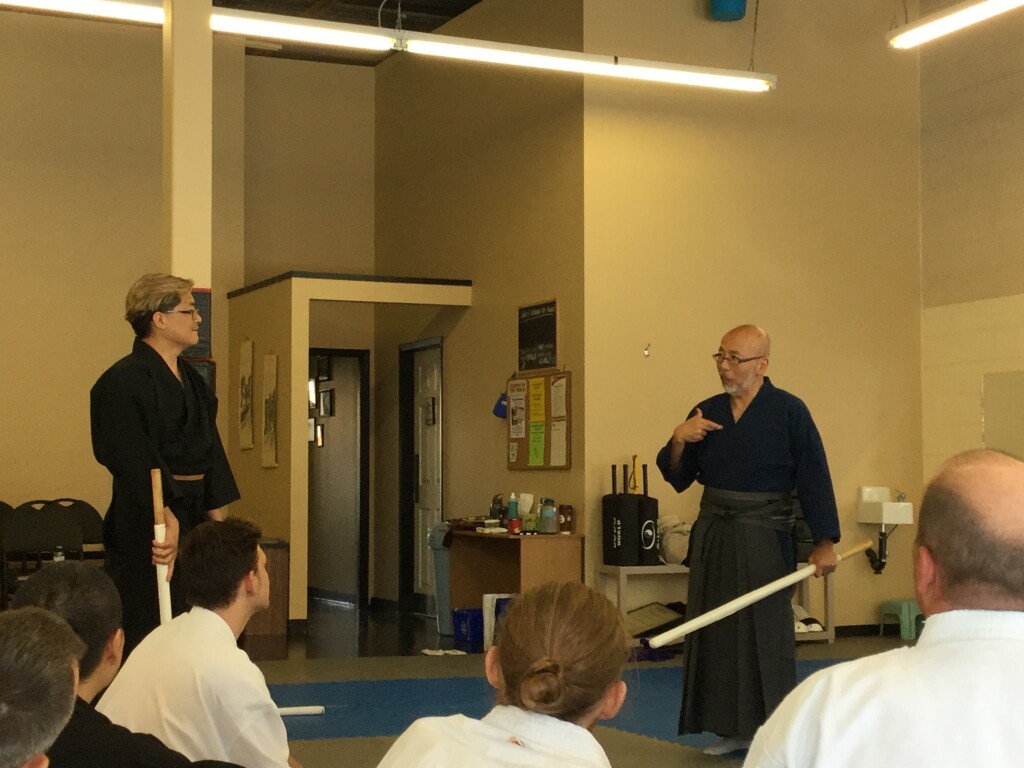

Kajitsuka Sensei talking about the spirit, mind, and hopes of our Founder

He said that Budo was born a long time ago, but it is not only for Japanese people. It’s for everyone in the world, and it is meant for peace and hope. By embracing the spirit of the founder and practicing the principles of Zen through the practice of kata, we can eventually become experts in being good human beings in the world.”

So I think from this interview, we can see how much he loves his art and how much he loves people. To want to help people, that requires unselfishness, like what was written above about feeling like a parent who cares for his or her children. We again see love.

In 2016, Kajitsuka Sensei came to Toronto once again and gave a seminar in Shingan Ryu. He expanded upon this idea of the dichotomy between taking life and preserving life.

A key idea came up in the post-seminar discussion about the origins of the art, what its original purpose was. Sensei remarked that Yagyu Shingan Ryu is really a very complete art, with two sides. What the students now focus on is only one side of the art, that of the destructive side of the art. Students focus on how to harm or hurt an aggressor. In this way, what they study now is incomplete. There is a constructive, more beneficial side of the art which has been partially lost. That side embraces healing. As Sensei explained, the art can be used to hurt, to destroy. But it also teaches how to heal a person.

Kajitsuka Sensei explaining about the two sides of the art: one of destruction and the other of healing

As an example, he talked about pressure points. Like he had demonstrated in the katas that the group had reviewed earlier in the day, the knowledge of pressure points plays an important role in submissions and take-downs. However, he also remarked that this same knowledge of pressure points was and can also be used to heal as evidenced by its use in acupuncture and such healing arts as shiatsu. Sensei encouraged the Shingan Ryu practitioners to not just view the art as a destructive one, but to look into its more beneficial side as well.

The knowledge of pressure points plays an important role in submissions and take-downs

Being empathetic, caring is also a part of budo. People don’t realize this. That is another form of love.

Sugino Sensei once said: “Budo training begins with courtesy and it ends with courtesy.”

Courtesy, respect, are very important values in budo. It is the backbone of the spirit of Bushido, the Code of the Warrior, of the samurai.

Courtesy and gratitude in budo is found in the practice of Reiho: the etiquette of bowing

And he went on to say:

“Courtesy is worshipping the gods, respecting people, revealing your heart because according to this, various virtues will grow in you. From the beginning, the roots of the Japanese spirit can be said to be worshipping the gods, having belief, and respectful worship from a thankful heart.”

This belief, worship, faith, thankfulness, and revealing your heart, are all forms of love. And it is unselfishness: not thinking of yourself but of others, and of the gods.

In Yagyu Shinkage Ryu, this kind of respect is built into the style and the art. Kajitsuka Sensei said:

“The important thing is that both Muneyoshi (the 2nd headmaster) and Kamiizumi (the Founder) experienced pain as a loser. And they wished for peace from the bottom of their heart, wished to change the sword from a tool to kill humans to a tool to bring up humans. By these two people, Shinkage Ryu has evolved into a peace-making sword, a sword that makes the most of people.”

This faith, revealing your heart, thankfulness, and respect, are all part of the spirit of Yagyu Shinkage-ryu

In other words, these men who fought during the Warring States Period saw the death and destruction that occurs when you are on the losing side and that more than anything else, motivated them to find a better way to exist in this world and cross this journey called life, than fighting and killing. A peace-making sword, a tool to bring up human beings and make the most of them. That is love… again. And respect.

So for a teacher, these are very important traits to have. Your students are like your kids in a way and you, as the teacher, are in some ways like a parent. Are you just educating them? Yes. But we are also at the same time raising them with values, like a sense of ethics and morality, and beliefs, like philosophies that the style believes in.

Budo education is also ethical: raising good citizens of the world

Is your job to teach them how to cut, cut and cut? Yes. That is the technical education you give them. But it is also your job to teach them “is it right to kill?” That, on the other hand, is the socialization into the beliefs and values that your style holds dear. That is the moral and spiritual education that you give them.

In public education, as a school teacher, we educate them in math and the abc’s of language. But we also need the parents’ help because they have the important job of raising their kids with a sense of morals and norms. In martial arts, as teachers, we need to do both jobs: the educating and the raising. This is the unselfishness of the teacher as parent: the spirit of giving and nurturing.

“Is it right to kill?” That is the socialization into beliefs and values: the moral and spiritual education in budo

————————————————————————————————————–

The seventh section is the Pioneer:

“Educators must have the spirit of pioneers, who thrive in uncharted territory.”

Kajitsuka Sensei’s Rule #4 is: “Don’t be afraid.”

This is about being brave. Remember his analogy about climbing that mountain? And remember Yagyu Nobuharu’s analogy about once you reach the top of your mountain, you will see another. So now you must go climb that one. This was his analogy of Yagyu Sekishusai’s philosophy that you must improve over yourself of yesterday. It is easy to stay put. But the Yagyu way is to keep striving. I went to Brock University here in Canada and that school’s motto is “Surgite!” which means “push on!’ We must strive forward. We keep climbing that mountain. And often, you do so alone. As I said, the journey in budo can be a lonely road.

Being brave is also about being courageous. As a teacher, things don’t happen unless we make them happen, unless we do them and create them. We are the starters, the initiators, the creators. Being a creator is being a pioneer. What is the definition of a pioneer? It is: “a person who begins or helps develop something new and prepares the way for others to follow.”

A pioneering spirit: starting a new tradition in Saskatchewan

And being the pioneers, we are also, at the same time, setting the standard. In many ways, we have to be the model and example, because there is no one else doing it before us. This is leadership. Being a teacher in many instances involves being a leader. A perfect example is starting up and running your dojo. A very scary proposition. And not many can do this. You need a can-do spirit and lots of confidence and a dash of courage to venture out on your own.

How did I come to this realization about being brave? It is actually built into the philosophy of Yagyu Shinkage Ryu. Remember Yagyu Nobuharu, the 21st Headmaster, when he gave his speech at the United Nations? He went on to give more details about the philosophy of our style. Let me read this one:

“I’d like to touch now on some of the components of the Yagyu Shinkage Ryu. An ancestor, Yagyu Sekishusai inherited the headmastership of Shinkage Ryu from Kamiizumi Nobutsuna. In a book on secret Yagyu techniques written by Sekishusai (Motsujimi Shudan Kudensho (没茲味手段口伝書), there is an introduction titled the go goh ken (五合剣). In it, he writes that one must be brave. The real meaning of this is to be free of fear of anything. If we are controlled by others, we can’t be flexible or free which is very important in a fight. If we are not brave in a real sense, we have no chance of victory. When you stand in front of an opponent you have a situation where you push or are pushed by him. If you are pushed, you can’t win. In actual life, in a normal situation, we act freely. Like breathing, you don’t have to think about inhaling or exhaling, this is a natural situation. With this kind of mind, even when in battle, then you can watch the opponent closely and detect his movement so you can give a proper response. Braveness is built into yourself but many things can prevent it. This braveness is the first point Sekishusai discussed.”

Being brave is to be free of fear. If we are controlled by our fears and our emotions, we can’t be flexible or free which is very important in a fight.

In fact, Yagyu Sekishusai also said in another document, his “100 Poems on The Art of War”, that a sword fight will eventually boil down into only 2 things: Bravery or Cowardice. Like in your iaido, or any sword style, you learn hundreds of techniques and strategies, secret moves and fancy techniques, 50 or more katas. But in the end, it will come down to only two things: are you brave or are you a coward?

Being a pioneer can also involve doing something unconventional, unique, new. So you must be prepared and have the courage to face the world alone. Bravery again. Like the initial description says: “thrive in uncharted territory.” It’s scary to be alone, doing it by yourself. But a pioneer lights the way. That takes courage, bravery. Don’t be afraid. It will come down to two things: bravery or cowardice…

This is the spirit of the teacher as pioneer: the spirit of lighting the way.

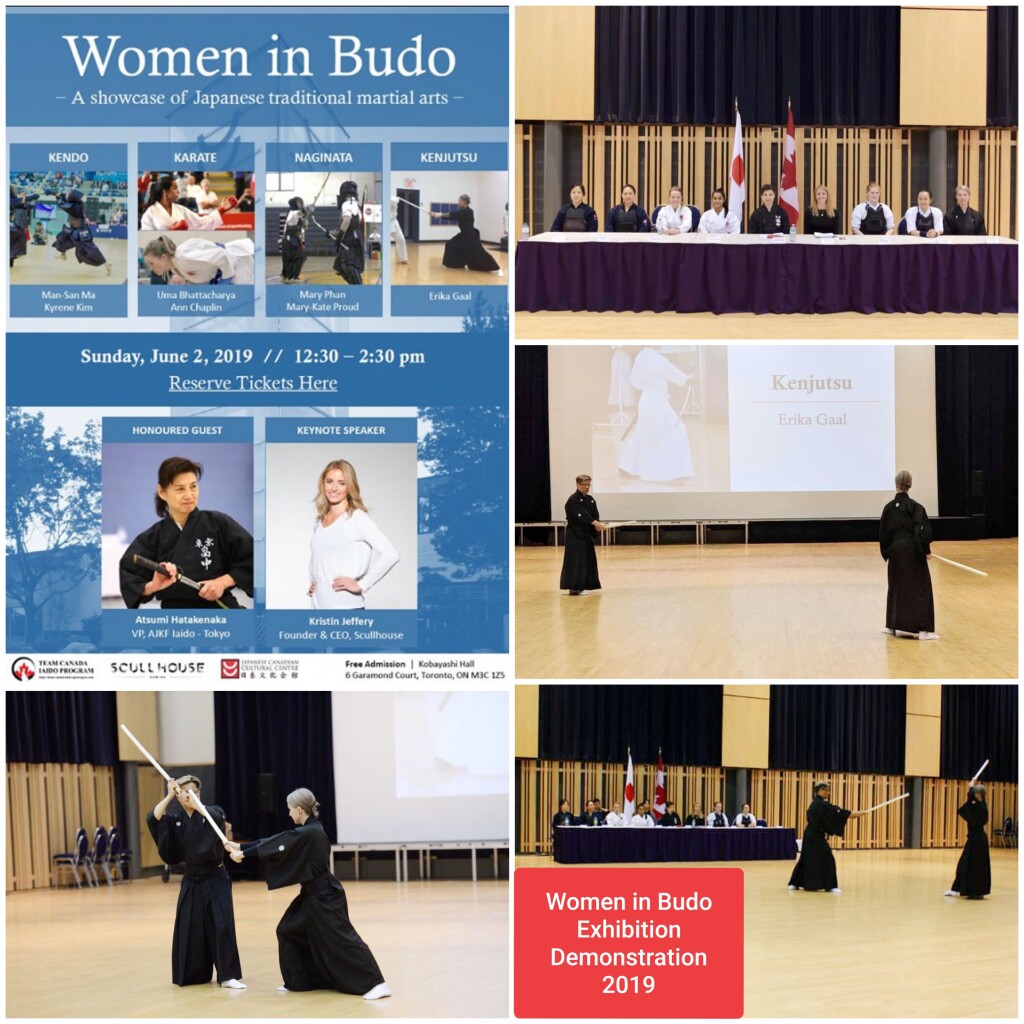

Lighting the way: a historic moment when we showcased our art for the first time to a national audience, the sword arts community of Canada, at a big, high-profile event

————————————————————————————————————–

The eighth and last section is the Innovator:

“Educators must have the courage of an innovator to continuously wonder “what if…” and not be afraid to fail as part of the process.”

Fear of failure. Fear. Like they say in the famous book and movie Dune: “fear is the mind-killer.”

Like I mentioned in the previous section, to create, to innovate, takes courage. You must fight your fear.

To start a new dojo, to start a new group, to break free from an association that you have been with for many years and go in a new direction; all these things take courage.

Starting a new group in Ottawa: a time for courage, hope, and faith

Kajitsuka Sensei’s Rule #5 is: “Try new things.”

Let’s recall what Yagyu Nobuharu Sensei said:

“Sekishusai said that you should surpass yourself that you were yesterday. A continuous improvement of the self is the way of the Yagyu Shinkage Ryu. In many cases we get satisfied when we reach a certain level. You must not be satisfied to reach one level of skill or only one target. Instead you must keep trying to improve and eventually you will find something to push yourself forward from within. Continuously trying to improve at the sword is related to the same effort made in Zen training. Training in the sword, in Yagyu Shinkage Ryu means a constant improvement of the self through training in how to use the sword.”

So, the ideal budo spirit in our style is striving and reaching for greater heights. In our interview in 2008, we talked about the spirit of budo. In his words:

“Question: In your opinion, what is the fundamental philosophy or idea of budo?

Sensei: In the old styles, the techniques are of course important. But everyone knows the techniques. They have not changed. But from now on, finding something new is important.

Let’s take the word “kobudo”. What we do is classified as kobudo. It is formed of these kanji. “Ko” typically means “old”. Old usually implies dead, a dead art. But it is not old. It is not dead. It is still alive, today. I don’t like the term “ko”-budo. It is not dead. It is still living. It is still adapting. It will continue to live and it will adapt to the needs, demands and atmosphere of the times in which it finds itself. It adapts constantly. So, don’t be afraid of new things or trying new challenges or experiences. This is the essential spirit of budo.

In Japanese, we talk of “challenge”. This means about the spirit of striving and reaching for greater things, greater heights. Budo has survived by adapting to each era. To continue to survive, it has to adapt and keep adapting. All styles that stopped adapting, have died out. The Edo Line of Yagyu is no more, unfortunately. This is a prime example.”

At Haru Matsuri 2017, we had five groups participating: Yagyu Shingan Ryu Taijutsu, Tenshin Shoden Katori Shinto Ryu, Hyoho Niten Ichi Ryu, Takamura-ha Shindo Yoshin Ryu, and Yagyu Shinkage Ryu Heiho. Our first Koryu Friendship Demo in Toronto! Trying new experiences is the essential spirit of budo.

I really like that. Let’s break down what he said. Sensei said that finding something new is important. Just like my conversation with my professor. She said that we ask more questions to push our current state of knowledge further, advancing the knowledge base.

Kajitsuka Sensei said that kobudo is not dead but very much alive. And it keeps living because it keeps adapting to “the needs, demands, and atmosphere of the times”. This is your new trends in Paris idea. Students hate it, all the changes. But these changes are necessary.

Sensei said that the spirit of budo is “the spirit of striving and reaching for greater things, greater heights.” So this echoes Sekishusai’s idea of constantly improving yourself, being better than you were yesterday.

Japan Trip 2017: Our members travelled to the other side of the world, to experience a different culture and way of life. It takes bravery to face the unknown

All this takes bravery, to face the unknown. To challenge oneself. To start a new dojo. To go in a new direction. To try a new approach. Kajitsuka Sensei also said to not be afraid of new things or “trying new challenges or experiences”. Like the definition of this section: you need to have the courage of the innovator. That is also part of being a teacher.

This is the courage of the teacher as innovator: the spirit of not being afraid.

————————————————————————————————————–

In conclusion, this graphic represents well the ideal make-up of a teacher. It also lays out the ideal traits and characteristics that teachers should aspire to.

It encourages us to be:

1) An Adventurer: To try new things, embrace change, and keep improving yourself.

2) A Scientist: To be disciplined and dedicated in your craft and through this understanding, to craft a blueprint for the students.

3) A Storyteller: To tell the stories that change their life.

4) A Teacher: To inspire them and to light that fire in them.

5) A Researcher: To continually do research and advance knowledge.

6) A Parent: To take your students under your wing, guide and raise them to be upstanding practitioners of the Way.

7) A Pioneer: To be the brave one to forge ahead, and to light the way.

8) An Innovator: To not be afraid of change and to do new things.

Just being a teacher who shows up to work, discharges his or her duty and then goes home is just punching a clock. And there are many teachers like that.

I have served for many years as an Associate Teacher (which is a mentor) for many Teacher-Candidates (which are interns), mentoring and instructing young teachers who are just entering the profession. The Ministry of Education wants me to instruct them on how to make a lesson plan and deliver it (lesson planning and execution). To make sure they understand the Ontario curriculum. To know the latest teaching techniques and technologies. To know about the Education Law and how not to break it. These are all technical things.

They can do that through their training in Teacher’s College. But what they don’t learn there is how to manage people, students in this particular instance. That you learn through experience, watching a master teacher do it. And when you are working with people, a lot of what I teach them is exactly a lot of what you see in this chart: how to try new things and not be afraid to fail, to inspire and lead, to guide students, to lead by example by yourself being disciplined and dedicated, showing the students a formula on how to succeed at school, and so on.

We learn from our teachers through experience, watching our Masters teach, and we become like them

Isn’t it interesting that in this chart, look at the highlighted words for each modality.

1) The Adventurer: Heart

2) The Scientist: Mind

3) The Storyteller: Imagination

4) The Teacher: Soul

5) The Researcher: Curiosity

6) The Parent: Unselfishness

7) The Pioneer: Spirit

8) The Innovator: Courage

These words do not pertain to technical aspects of teaching, like how to plan a lesson or to know about the curriculum or the latest teaching techniques. No, these words are about virtues, traits, which are emotional and spiritual parts of your character, your self, your being, your soul.

Let me read one final anecdote from a book I read online called “The Courage to Teach”.

“After three decades of trying to learn my craft, every class comes down to this: my students and I, face to face, engaged in an ancient and exacting exchange called education. The techniques I have mastered do not disappear, but neither do they suffice. Face to face with my students, only one resource is at my immediate command: my identity, my selfhood. Here is a secret hidden in plain sight: good teaching cannot be reduced to technique; good teaching comes from the identity and integrity of the teacher. In every class I teach, my ability to connect with my students, and to connect them with the subject, depends less on the methods I use than on the degree to which I know and trust my selfhood—and am willing to make it available and vulnerable in the service of learning.

Teaching is connecting with students

My evidence for this claim comes, in part, from years of asking students to tell me about their good teachers. As I listen to those stories, it becomes impossible to claim that all good teachers use similar techniques: some lecture non-stop and others speak very little, some stay close to their material and others loose the imagination, some teach with the carrot and others with the stick.

But in every story I have heard, good teachers share one trait: a strong sense of personal identity infuses their work. “Dr. A is really there when she teaches,” a student tells me, or “Mr. B has such enthusiasm for his subject,” or “You can tell that this is really Prof. C’s life.”

“Good teachers share one trait: a strong sense of personal identity infuses their work.”

One student I heard about said she could not describe her good teachers because they were so different from each other. But she could describe her bad teachers because they were all the same: “Their words float somewhere in front of their faces, like the speech balloons in cartoons.” With one remarkable image she said it all. Bad teachers distance themselves from the subject they are teaching—and, in the process, from their students.

Good teachers join self, subject, and students in the fabric of life because they teach from an integral and undivided self; they manifest in their own lives, and evoke in their students, a “capacity for connectedness.” They are able to weave a complex web of connections between themselves, their subjects, and their students, so that students can learn to weave a world for themselves.”

You can be a fantastic martial artist but not be able to teach it. Because teaching is the art of reaching students. So whether it is teaching martial arts or teaching language arts, it is the same. Teaching is an art form all its own. And deep down, it is about spirit, passion, and love.