Mexico Seminar 2016

December 2016

Tijuana, Mexico

copyright © 2017 Douglas Tong, all rights reserved.

Mexico Seminar 2016

______________________________________________________

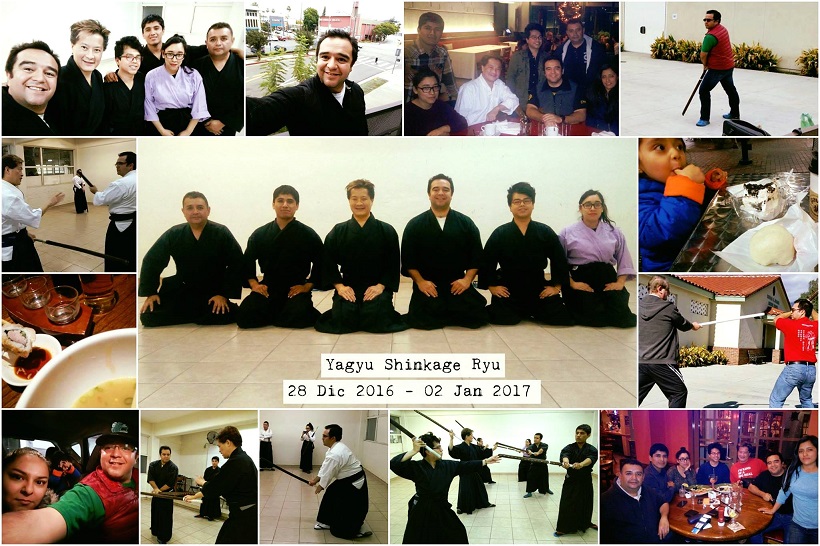

In December of 2016, Tong Sensei once again travelled to Tijuana to conduct private seminars in Yagyu Shinkage Ryu kenjutsu. Below is copied the seminar report courtesy of Muso Dojo, our official keikokai in Mexico. We have also included our own commentary to support the text and add further details to the story.

To view the original seminar report in Spanish by Muso Dojo, go here:

reporte-de-seminario-shinkage-ryu-kenjutsu-2016-con-sensei-douglas-tong

______________________________________________________

SHINKAGE RYU KENJUTSU 2016 WITH SENSEI DOUGLAS TONG

SEMINAR REPORT

Muso Dojo / 無想道場·

Saturday, January 21, 2017

On the 28th, 29th and 30th of December 2016, we were fortunate to train for the third time in our city with our Master-in-Arms, Sensei Douglas Tong, Director of Tokumeikan, the Association to which Muso Dojo belongs. Tokumeikan is directly attached to Arakido, a classical budo association directed By Sensei Yasushi Kajitsuka, heir of the Ohtsubo Branch of the main Owari Line of Yagyu Shinkage Ryu and the Edo Line of Yagyu Shingan Ryu. In addition, Sensei Kajitsuka is also the Secretary-General of the Nihon Kobudo Shinkokai, the Japanese association that recognizes and gives validity to the veracity and existence of any style that calls itself a traditional or classical Japanese martial art.

San Diego Airport

After picking up Sensei Douglas at San Diego Airport, we began talking about the plan for the upcoming training sessions and started in Tijuana with the practice of Shinkage Ryu. The reunion of Sensei Douglas with my students as always was attentive and emotional. We began to train and review the “homework” that we were given last year and for which we had to refine so as to make the most of his visit here this year.

Tokumeikan: This is our distance-learning model. When we come, we assign the homework for the year. It is the student’s job to ensure that the homework is done for when we next meet. If it has been done, then we can move onto the next item on the agenda. If not, then we need to revisit it and ensure that this step has been learned. It is not a new model. It is the same model used by our Founder Kamiizumi Nobutsuna in 1565 when he assigned some homework for his disciple Yagyu Munetoshi to research for the next year. When Master Kamiizumi came back the next year, disciple Munetoshi was ready and showed his Master what he had learned. And the rest is history.

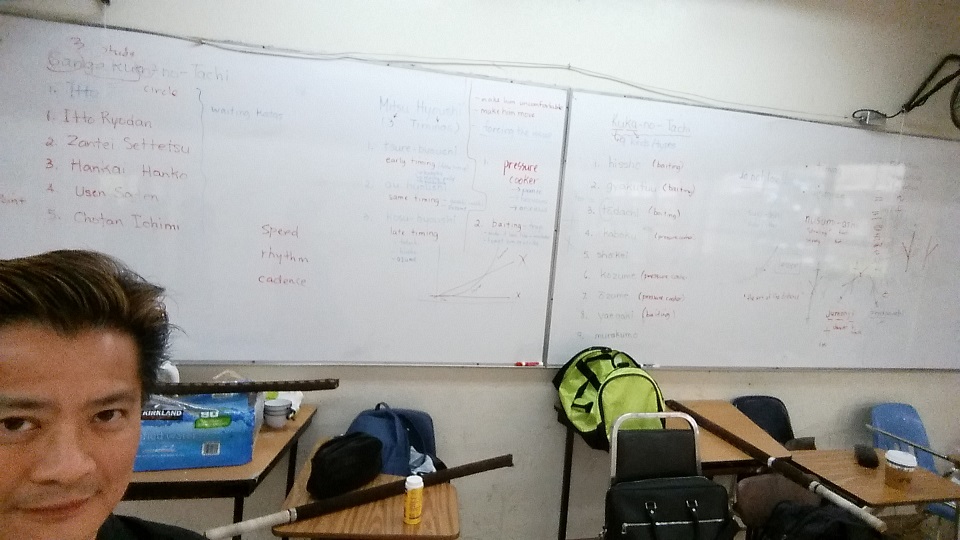

Tong Sensei checking the homework that was assigned

By means of his methodical, specific and friendly style of teaching, we were able to polish the details that led us to the good practice of our Kihon (fundamentals) and that allows us to give continuity to the tradition that we have the fortune to train in, Yagyu Shinkage Ryu kenjutsu, a martial tradition of more than 400 years, being the style adopted by the Tokugawa Shogun and which directly shaped the policies that would ensure the longest reigning government in the history of Japan.

Polishing up some important details

As we progressed through the days, we were able to train in detail each of the kata (the forms) that give life and structure to our style. We explored the different levels of Sangakuen-no-Tachi (the first set of kata) and these explorations were accompanied by explanations from the Heiho Kadensho (the Hereditary Book of the Art of War), a complex vision of the philosophy that guided Japan to become a unified and solid nation. This book Heiho Kadensho written by Yagyu Munenori in 1632 gives the principles for battle, good governance and, as we saw constantly in the seminar taught by Sensei Douglas, it also gives us the mental exercises to complement the physical training.

Tokumeikan: Philosophy drives technique. Issues like how to cut, how to strike, sword-wielding mechanics and methodology, are all determined by philosophy. Philosophy also drives tactics. When to cut, how to move the opponent, how to react, attacking strategy and defensive strategy all follow the philosophy of the Founder who created the style and his vision of what a swordfight looks like. We are blessed that the philosophy of the style is codified in the Heiho Kadensho. It is the blueprint that allows us to understand why we do the things we do in this style. Hence, it is necessary to accompany the technical lessons with philosophical ones as well, to add the meat to the bones as they say.

Melding together technique with tactics, strategy, and philosophy

After the study of Sangakuen-no-Tachi, we began with the training of a new compendium of kata called Kuka-no-Tachi. This compendium of kata literally changed our way of seeing, walking and training. Training in the Sangakuen-no-Tachi set first gave us the principles to have the structure and method of training to observe and train Kuka-no-Tachi, a set of nine kata that give the bases of the combat and that make it possible to begin to understand the strategy behind Shinkage Ryu.

Kuka-no-Tachi: a whole new ball of wax

As we learned each kata, we were able to see the secret methods of style. Anyone can find and see these kata online and on social media. However, the details and the philosophy behind the performances and embedded in the kata themselves are only available and transmissible through one form of teaching in the martial arts: through the Sensei-Deshi relationship, the close relationship between teacher and student.

Tokumeikan: As my old master Yoshio Sugino Sensei of Tenshin Shoden Katori Shinto Ryu said, “Traditionally, the teaching of budo was from teacher to student, heart to heart…”

Teaching and learning is still one-to-one

The connection from one session to another occurred in a fluid and enjoyable way. Part of the training is to talk with the Master, to live with him, to ask, to respond, and to analyze. This type of mental training helps to change the training from just a simple physical practice like that found in sports clubs or certain hobbies like skiing, and transforms it into more of a lifestyle, a way of thinking and acting.

Tokumeikan: Bushido (the Way of the Warrior) is a concept which describes the samurai way of life, and this Way encompasses samurai moral values “most commonly stressing some combination of frugality, loyalty, martial arts mastery, and honor.” It is a Code of Virtues, a Code of Ethics, a Code of Values that came to govern the life of the samurai. But it is an unwritten code, one learned through example from a more experienced senior or master. This way of life, this life style, is one that has been passed down from teacher to student since the Middle Ages. Serious students of budo still follow the Code. Like Hector says, talking with the Master, being with him, beside him even in silence, asking questions, responding, discussions during dinner, off-hand remarks while traveling together, observations during a demonstration or training session, even idle chit-chat during coffee, are all valuable experiences that cannot be overlooked. They are equally if not more important than the technical lessons themselves because these intimate experiences are more about socialization, inheriting the values, customs, norms, and ideologies of the samurai world, of the profession so to speak. Socialization is defined as “the means by which social and cultural continuity are attained”. That is why the samurai ideal and ideology still exist to this day. It has been dutifully passed down through the generations, from master to apprentice. This is why being an apprentice, a disciple, ultimately an uchi-deshi (an “inside” student), to a Master is so important. Watch this excellent short video about the lives of two uchi-deshi and witness this socialization process:

Aikido Uchideshi by Empty Mind Films

At lunch and dinner time, Sensei Douglas took the opportunity to delve into the philosophy of our style and used every moment to use it as a teaching-learning opportunity.

Enjoying some late-night food and pleasant conversation at an all-night roadside taco stand

The last day of training we did review and got corrections and enjoyed another day of Shinkage Ryu training. At the end of the seminar, we had a delicious dinner in one of the many places that Tijuana offers. We enjoyed a meal together as a family. That same day, one of our students was invited to submit his application to officially join Arakido under the direct tutelage of our Soke and thus to continue this tradition and lifestyle that is available to only the most diligent students.

Teacher and disciple: a special relationship

After dinner, Sensei Douglas said goodbye to us by inviting us to continue the training by persevering in our study of the philosophy of Shinkage Ryu and in keeping the art alive through our diligent and continuous practice.

Diligent and continuous practice is the road to success

This was a seminar of great learning. We are very grateful to Sensei Douglas for making this great art of Shinkage Ryu Heiho available to us, and also for opening the door for us to study Shingan Ryu Taijutsu. We look forward to the next seminar with Sensei Tong which has now become a regular and highly-anticipated annual event for our Dojo.

HÉCTOR BRAVO, MUSO DOJO. TIJUANA, MÉXICO.

Tokumeikan: I like what Hector said: “We enjoyed a meal together as a family.” In the end, this is what learning a certain style is about, family. A style like Yagyu Shinkage Ryu is a family style, the style of a clan. And it has been passed down within the family for 500 years. Joining a dojo in Japan is like joining a clan, a family. A successful dojo, or organization, operates somewhat like a family. They grow together, have fun together, learn together, enjoy the time together. I really felt the togetherness of the group on this trip. They are a cohesive group and they are developing and progressing well. They are blazing a trail and have established the Yagyu presence in Mexico. If they can keep this family together, they will certainly have a bright future.

Having dinner as a family

______________________________________________________

Addendum:

The issue of socialization is so important in the study of budo. You can learn all sorts of moves and flashy techniques from YouTube and books and social media. It’s all out there now. But what separates the casual amateur who wants to show off his or her flashy sword-wielding ability to legions of inconstant followers on Instagram or Facebook and the hardcore, serious, long-term student of a legitimate koryu? It is this socialization into the values of the samurai, the Code of the Bushi (Warrior). They toil in obscurity, practicing continuously the art of death with a blade, following an ancient code of ethics espousing virtues like respect, honour, duty, integrity, self-control. It is truly a way of life and one that is learned at the foot of a Master. Here is one article that perfectly explains this socialization or indoctrination into the Way:

I am a deshi

Written by: Hasuda Tomoka

1st year Junior high school student (approx. 13yrs old)

Miyazaki prefecture, Miyazaki city, Shujakukan dojo

Suddenly, after keiko one day my sensei said “you are my deshi.” I was surprised at the suddenness of words, but I was also happy that he called me “deshi.” However, I somehow felt strange. It’s because I didn’t actually understand the word “deshi” or what being one means or involves. I thought hard about the meaning of the word and searched out information about it in books and dictionaries. I discovered that “deshi” is part of a“teacher-student” relationship (師弟の関係). On one side of the coin we have the teacher – one with technical skill based on, and knowledge cultivated through experience – who imparts this through instruction; and on the other side we have the deshi, who learns from and studies under the teacher. In a dojo environment, the sensei are the teachers, and we are the deshi.

So, what is a deshi’s job? What is a deshi supposed to do? A deshi has many various jobs to learn, including seeing off and meeting the sensei when they come to the dojo (shiai), getting any shopping thats needed (for the dojo and/or sensei), taking care of various things around the sensei (to do with the dojo) etc. In kendo, for example, tidying up/putting away the sensei’s bogu and making sure he is comfortable are both part of the deshi’s job.

I started taking tea to the sensei after keiko when I was a 6th grade primary school student (11/12yrs old). This started because my sensei said “bring me tea,” but now it just natural happens. During that short interval, sensei gives me praise, or brings my bad points to attention.

We also talk a lot about non-kendo things as well. What my future dreams are, what’s going on at school, the taikai my sensei goes to, the change in seasons, etc all of these are valuable conversations for me. On the occasion that visitors came to keiko, I brought them tea as well. At that time I was told to sit in the corner and listen to the conversation (between the adults). I couldn’t really understand what was being talked about but my sensei said later “even if you can’t understand what’s being said, even if you are not part of the conversation, listening to other people’s stories and conversation is important. There will come a time when you will understand.” When he said this to me I pondered that the chance to listen in on these conversations was something different when compared to my usual daily life, and approached these chats with a new feeling.

Another thing that I pay attention to is when my sensei leaves by car (after keiko). When I see him off, I wait until I can no longer see his car before turning away. I learned this after watching how the Riot Squad Police treated their sensei (its possible she is talking about the elite tokuren kenshi in her prefecture).

By continuing to be a deshi like this I have learned some good things, for example: how to use language properly (i.e. learning to by polite in Japanese) and how to be sensitive to nuances in peoples conversations, so now I am at ease with speaking to people who are my superior (i.e. by rank, age, profession, etc). There are other things as well, for example I am able to think and predict what sensei will say/want next, and am already in motion before anything is actually said.

At one time, my sensei told me that deshi have responsibilities. I didn’t really understand what these could be and I thought about it to myself. I think a deshi’s responsibility/job is to keep what’s taught to them by their sensei and act within their limits, and to pass these teachings onto their kohai. I still don’t have the ability to do this, so in the meantime I will try my best at keiko, and aim to become a good sempai in the future.

At first I didn’t really know what it means to be a “deshi,” but thanks to everything that my sensei has taught me, I think I am getting closer to understanding the true meaning. Ever since becoming a deshi, my sensei has shouted at me a lot; but since there few people around to scold me, I am thankful that he is there, as I know it is for my own benefit.

From now on, through kendo and as a deshi/person, I want to keep learning about life.

Original Source: 剣道時代2011年4月。「私は弟子です」。蓮田和佳。

Online Source: i-am-a-deshi